Classroom Contagions: A Back-to-School Survival Guide

- Heather McSharry, PhD

- Aug 26

- 30 min read

Updated: Sep 9

Summary

Back-to-school season means new teachers, new friends…and a whole new round of germs. From runny noses to strep throats, pinkeye to flu, classrooms are a breeding ground for illness once the school bell rings. In this episode of Infectious Dose, Heather breaks down the most common fall outbreaks in kids, when to keep children home, and the prevention strategies that actually make a difference.

You’ll also hear about the role vaccines play in keeping kids healthy, what to do if masks aren’t welcome in your school, and how new attendance policies—like the controversial one in Tennessee—make it even harder for parents to do the right thing. This episode is a practical, parent-friendly guide to surviving sick season with sanity intact.

Listen here or scroll down to read full episode.

Full Episode

A freshly sharpened pencil. A backpack zipped tight. A shiny new lunchbox packed with snacks. It’s the first day of school. Kids file in, chattering, nervous, excited.

But hiding in the shuffle—something else arrives. It’s invisible, hitching a ride on a sneeze, tucked into a cough, smeared across a desk with sticky little fingers. By the end of the week, it’s spreading faster than gossip in the lunch line. Runny noses. Pink eyes. Sore throats. Tissues piling up like homework.

It’s not a math test, not a pop quiz. It’s the annual back-to-school outbreak season. And parents everywhere are bracing for it.

This is Classroom Contagions: A Back-to-School Survival Guide.

It's no mystery, kids go from being around just family or maybe a small summer camp group to suddenly sharing classrooms, cafeterias, and sports gear with hundreds of other kids. It’s like putting viruses on speed dating—they spread fast, and you end up dealing with a revolving door of tissues, coughs, and stomach bugs.

So in today’s episode, I want to walk you through what parents need to know about the most common illnesses that make the rounds every fall here in the U.S.—but I’ll also take a step back and highlight some school-based outbreaks that are especially common in other parts of the world, because not all my listeners are in the same classrooms or even the same countries. We’ll cover when it’s important to keep kids home, what simple prevention steps actually work, and where vaccines fit into the picture. And I’ll also touch on some tricky realities, like the politics of masking in schools and some school districts changing attendance policies in ways that can make parents’ lives harder.

Before we dive in, a quick note about how I’ll handle the ‘when to see the doctor’ sections. Sometimes, that advice is about when to go in for a diagnosis in the first place—like if your child has a sudden, painful sore throat that could be strep. Other times, it’s about when to go back if things take a bad turn while your child is already recovering at home—like if a usually mild virus suddenly gets worse. And for very common illnesses like the cold, where you probably wouldn’t see a doctor right away, I’ll flag the red-flag symptoms that mean it’s time to call even if you were planning to ride it out at home. In other words, think of this as a guide for both first visits and follow-ups, depending on the illness.

Transmission: Colds are caused by many different viruses, but rhinoviruses are the most common culprit. They spread easily through airborne droplets when someone coughs or sneezes and by touching contaminated surfaces and then touching your nose, mouth, or eyes.

Symptoms: The common cold is one of the most frequent illnesses in kids—up to 6–8 times a year in younger children and 2–3 times a year in adults. Symptoms include a runny or stuffy nose, sore throat, sneezing, cough, and sometimes a mild fever in children.

When to See the Doctor: Call your doctor if cold symptoms last more than 10 days, if your child has difficulty breathing, shows signs of dehydration, or if a fever worsens or comes back after seeming to improve.

Prevention: Simple steps are the best defense: frequent handwashing, avoiding close contact with sick individuals, not touching the face, and ventilating indoor spaces when possible.

Treatment: There is no cure for the common cold—treatment focuses on helping your child feel better while the illness runs its course. Rest, plenty of fluids, and comfort measures like humidifiers or saline nasal sprays can ease symptoms. Over-the-counter fever and pain relievers such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen can also help if your child is uncomfortable. Antibiotics won’t work against colds, since they are caused by viruses. Most colds resolve on their own within 7–10 days, though coughs may linger a bit longer.

Possible Complications: Complications are rare but can include sinus infections, ear infections, or worsening of asthma symptoms.

Vaccines: Unfortunately, there is no vaccine for rhinoviruses. With more than a hundred different types and no lasting immunity after infection, creating a vaccine has proven extremely difficult.

Transmission: Influenza spreads quickly through droplets when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, and also via contaminated surfaces. People can pass the virus to others even before they show symptoms.

Symptoms: Unlike colds, the flu strikes suddenly and affects the whole body. Classic signs include high fever, chills, severe fatigue, headache, muscle and joint aches, cough, sore throat, congestion, and sometimes eye pain or sensitivity to light. Kids may look and feel much sicker than they would with a common cold.

When to See the Doctor: Seek medical advice if fever of 102°F (38.9°C) or higher persists, breathing becomes difficult, symptoms disappear and then come back worse, or if your child shows warning signs such as dehydration, rapid breathing, bluish skin, confusion, or unusual irritability. These signs are especially concerning in babies and toddlers.

Prevention: The annual flu vaccine is the best protection, updated each year to match circulating strains and reduce both risk and severity. Other preventive measures include handwashing, covering coughs and sneezes, keeping sick children home, and improving indoor ventilation.

Treatment: Antiviral medications like Tamiflu can help if started within 48 hours, especially in young children or high-risk groups. Most kids recover in about a week, but supportive care with fluids, rest, and fever reducers may be needed.

Possible Complications: The most serious complications involve the lungs. Influenza itself can cause primary viral pneumonia, or it can open the door to secondary bacterial pneumonia. Staphylococcus aureus—including MRSA—is a frequent culprit in these cases and carries a high risk of death, which is why doctors often choose antibiotics that cover it when pneumonia appears during flu season. Less common complications include heart, muscle, or nervous system problems, which can occur at any age. Prompt antiviral treatment helps reduce the risk of these outcomes, though drug resistance remains a challenge.

Vaccines: Yearly flu vaccination is recommended for everyone 6 months and older. It remains the most effective tool we have for preventing influenza and its complications.

Transmission: Primarily spreads through airborne particles and droplets when an infected person breathes, talks, coughs, or sneezes. It can also spread via contaminated surfaces, though this is less common.

Symptoms: In kids, symptoms can look like anything from a mild cold to a high fever with cough, sore throat, headache, or stomach upset. Loss of taste and smell is less common in kids than adults. Some children have no symptoms at all but can still spread the virus.

When to See the Doctor: Call if your child has difficulty breathing, persistent chest pain, confusion, inability to stay awake, dehydration, or bluish lips/skin. Children with underlying conditions like asthma, diabetes, or immune suppression should be monitored closely.

Prevention: Staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccination is still the best protection against severe illness. Good ventilation, masking when community transmission is high (if allowed in your school district), hand hygiene, and keeping kids home when sick all help limit spread.

Treatment: Most cases in kids are mild and managed at home with rest, fluids, and fever reducers. For high-risk children, antivirals like Paxlovid may be recommended by a doctor, but these are not routinely used in otherwise healthy kids.

Possible Complications: Rare but serious risks include MIS-C (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children), long COVID symptoms such as fatigue or concentration problems, and severe pneumonia.

Vaccines: COVID-19 vaccines remain recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The CDC recently downgraded them to “shared clinical decision-making,” but professional pediatric groups continue to support vaccination for eligible children. Boosters are adjusted as new variants emerge, so check with your pediatrician about what’s current.

Transmission: Respiratory enteroviruses—such as EV-D68, EV-A71, EV-C strains, and CV-A21—spread mainly through respiratory droplets and contact with contaminated surfaces, similar to the common cold.

Symptoms: These viruses often start like a mild cold, with runny nose, cough, and throat discomfort. In some children, especially those with asthma or weakened immunity, illness can progress to wheezing or pneumonia. EV-D68 in particular has been associated with wheezing and difficulty breathing. In very rare cases, some enteroviruses have been linked to serious neurological conditions such as acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), which causes sudden limb weakness.

When to See the Doctor: Call your child’s doctor if they develop breathing trouble, wheezing, new neurologic symptoms like limb weakness, or if their illn ess suddenly worsens or lasts longer than you’d expect for “just a cold.”

Prevention: There are no vaccines or antiviral treatments available for respiratory enteroviruses. Prevention depends on everyday habits: good handwashing, covering coughs and sneezes, staying home when sick, and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces.

Treatment: No specific treatment exists. Supportive care—rest, fluids, fever reducers, and comfort measures—helps children recover while their immune system fights off the infection.

Possible Complications: Most children recover fully without complications. However, in rare cases, these infections can lead to severe respiratory illness or neurologic problems like AFM, making awareness and early medical care important.

Vaccines: There is no vaccine available for respiratory enteroviruses.

Transmission: Hand, foot, and mouth disease is caused by enteroviruses in the Picornaviridae family—most often coxsackievirus A16, and sometimes EV‑71 or Coxsackie A6—with the possibility of more severe outbreaks in some regions. The virus spreads easily through the fecal‑oral or oral‑oral routes, respiratory droplets, saliva, fluid from blisters, or contact with contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is typically 3 to 6 days, and people are most contagious during the first week of symptoms—though virus shedding in stool can last up to 6–12 weeks.

Symptoms: Symptoms begin with a low-grade fever and flu-like signs 3 to 5 days after exposure, followed 1–2 days later by painful mouth sores—often on the tongue, gums, or inside cheeks—and a rash with red or blistering spots on the hands, feet, and sometimes buttocks. The rash can vary in appearance depending on skin tone and may include small bumps or blisters.

When to See the Doctor: HFMD is usually mild and self-resolves in 7–10 days. But call your pediatrician if:

Your child is under six months or immunocompromised

Fever persists beyond 3 days

Mouth sores severely limit drinking or eating

Symptoms remain uncomfortable or last more than 10 days

Prevention: There’s no vaccine currently available in the U.S.. Prevention depends on:

Frequent handwashing, especially after diaper changes or bathroom use

Disinfecting contaminated surfaces and items with dilute bleach solutions

Keeping sick children home until blisters have dried up

Avoiding sharing cups, utensils, and towels

Treatment: No specific antiviral treatments exist. Care is supportive:

Keep your child hydrated—mouth sores can make swallowing painful

Offer liquid or soft foods that are gentle on the mouth

Use over-the-counter pain relievers like acetaminophen or ibuprofen to ease fever and discomfort (don’t give aspirin to children)

Most recover within a week to ten days

Possible Complications: Complications are rare but can include:

Dehydration, especially if mouth pain limits drinking

Nail shedding (onychomadesis), usually temporary

In rare cases, neurological issues like viral meningitis, encephalitis, or paralysis-like symptoms have occurred—most notably associated with EV‑A71 in large outbreaks.

Vaccines: No vaccines are approved in the U.S., though EV‑71 vaccines have been used in China, and researchers are working on broader preventive strategies

Transmission: Norovirus spreads rapidly—primarily through the fecal-oral route. This can happen via contaminated food, water, surfaces, or direct contact with someone who’s infected. It can also become airborne during vomiting. People are highly contagious once symptoms begin and can still spread the virus for days afterward.

Symptoms: Symptoms usually start abruptly, 12 to 48 hours after exposure. Expect gastrointestinal distress—nausea, vomiting, stomach cramping, and diarrhea—often accompanied by low-grade fever, headaches, muscle aches, and fatigue. These typically last one to three days and resolve on their own.

When to See the Doctor: Most children recover at home, but reach out to your pediatrician if:

Vomiting or diarrhea lasts more than 2–3 days

Your child shows signs of dehydration: dry lips, fewer wet diapers or dark urine

High fever over 102°F

Blood appears in vomit or stool

Severe stomach pain

Especially urgent in newborns—contact the doctor sooner in such cases

Prevention: Hand washing with soap and water is your best line of defense—hand sanitizers don’t destroy norovirus. Disinfect contaminated surfaces with bleach solutions and keep sick kids home for at least 48 hours after symptoms stop. Avoid shared food, utensils, or bathrooms if possible.

Treatment: There’s no medicine to cure norovirus. Treatment is supportive: the main goal is to stay hydrated. Offer oral rehydration solutions or clear liquids like water or broth, starting slowly after vomiting. In severe cases, IV fluids may be necessary. Rest, patience, and gentle reintroduction of bland foods as tolerated can help recovery.

Possible Complications: Complications are rare but dehydration is the top concern—especially in young children or those with weakened immune systems. Severe dehydration can become a medical emergency, potentially leading to lethargy, rapid heart rate, or shock.

Vaccines: There are currently no vaccines for norovirus. Research continues, and early vaccine candidates are being studied, but none are available for use yet.

Transmission: RSV is a highly contagious respiratory virus that spreads through droplets when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, as well as via direct contact with contaminated surfaces. Nearly all children have had RSV at least once by age two, and immunity after infection doesn’t last, so repeat infections are common.

Symptoms: Symptoms start like a cold and typically appear 4–6 days after exposure: runny nose, congestion, decreased appetite, coughing, sneezing, and fever. In infants, RSV can also cause wheezing and breathing difficulty—sometimes the only signs are irritability and reduced activity.

When to See the Doctor: Most cases can be managed at home, but seek medical attention if your child shows signs of respiratory distress (rapid or noisy breathing, retractions, nasal flaring), dehydration (fewer wet diapers, dark urine), chest pain, blue-tinged lips, or a high fever that won’t go down. Babies under 6 months, and any children with underlying conditions, may need evaluation sooner.

Prevention: Unlike colds, RSV may also be prevented in high-risk infants through monoclonal antibody treatments. Everyday prevention remains essential: frequent handwashing, covering coughs, disinfecting high-touch surfaces, avoiding crowded places during RSV season, and avoiding exposure to secondhand smoke.

Treatment: There is no specific antiviral treatment for RSV—care is supportive. Offer fluids and over-the-counter fever reducers (acetaminophen or ibuprofen), use nasal saline and gentle suction for congestion, and consider a cool-mist humidifier. In severe cases (especially dehydrated infants or those with breathing trouble), medical care may include oxygen or IV fluids.

Possible Complications: While most children recover fully, RSV can cause bronchiolitis (inflammation of small airways), pneumonia, apnea (especially in very young infants), and ear infections. Severe RSV in infancy is associated with long-term risks like wheezing, asthma, and chronic allergies. In rare cases, neurologic complications such as seizures may also occur.

Vaccines or Preventive Agents:

Nirsevimab (Beyfortus): A monoclonal antibody approved for infants under 8 months entering their first RSV season. It reduces serious lower respiratory RSV illness by around 70–75%.

Palivizumab (Synagis): Another antibody given to high-risk infants—premature babies or those with lung or heart conditions. It also lowers hospitalization risks.

Adult and maternal RSV vaccines: Not for kids directly—but safe RSV vaccines are now available for pregnant individuals (to protect newborns) and older adults at risk of severe RSV.

Transmission: Infectious conjunctivitis—commonly known as pink eye—spreads easily in schools. It can be viral or bacterial and is passed through respiratory droplets, contaminated hands, shared towels or toys, and even swimming pools. Viral cases, such as those caused by adenovirus, are especially contagious and may spread for days.

Symptoms: Symptoms typically include pink or red eyes, itching or burning, tearing, eyelid swelling, light sensitivity, and discharge—watery for viral cases, thicker and possibly sticky for bacterial types.

When to See the Doctor: Seek medical care if your child experiences eye pain, a painful sensitivity to light, changes in vision, symptoms longer than a week, or fever accompanying the eye infection.

Prevention: Frequent handwashing—especially after touching eyes—is your best defense. Avoid sharing towels, pillows, or makeup, and teach children to steer clear of touching their eyes.

Treatment:

Viral conjunctivitis typically resolves on its own within 1–2 weeks. Cool compresses and artificial tears can help ease discomfort.

Bacterial conjunctivitis may require antibiotic eye drops or ointment, which can shorten the illness and reduce contagion.

Possible Complications: Though rare, complications can include corneal involvement (especially with certain adenoviral strains), vision changes, or bacterial spread requiring more serious intervention.

Vaccines: There are no vaccines for conjunctivitis itself, but vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), pneumococcus, and meningococcus may prevent some eye infections in young children.

Transmission: Strep throat is caused by group A Streptococcus bacteria (GAS). It spreads through respiratory droplets—like when someone coughs, sneezes, or talks—or via contact with shared surfaces, utensils, or drinks. It’s most common among school-aged children (5–15 years old) and spreads readily in crowded places like classrooms and daycares.

Symptoms: Strep throat usually hits suddenly: a painful sore throat, trouble swallowing, fever, red and swollen tonsils sometimes with white patches or streaks (exudate), swollen lymph nodes in the neck, and sometimes red spots on the roof of the mouth (petechiae). Children may also have headaches, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, or a sandpaper-like rash known as scarlet fever. Unlike viral sore throats, strep usually doesn’t come with a cough or runny nose.

When to See the Doctor: Call your pediatrician if your child has a sudden, painful sore throat, fever, swollen glands, or a rash—especially without cold-like symptoms. The doctor will likely confirm strep with a throat swab or rapid test before prescribing antibiotics.

Prevention: There’s no vaccine for strep throat, though researchers are working on one. Prevention hinges on everyday habits: good handwashing, covering coughs and sneezes, not sharing utensils or drinks, and disinfecting commonly touched surfaces. Once treatment begins—typically with penicillin or amoxicillin—contagiousness drops within 12 hours.

Treatment: Strep throat requires antibiotics. Penicillin or amoxicillin are the standard treatments and quickly relieve symptoms while also preventing complications. Children usually start to feel better within 24–48 hours. Supportive care—like rest, fluids, and fever reducers—can also help with comfort.

Possible Complications: When treated promptly, strep throat usually resolves quickly and safely. But without treatment, it can lead to complications like rheumatic fever (affecting the heart, joints, and skin), kidney inflammation (glomerulonephritis), ear infections, abscesses around the tonsils, and—in rare cases—invasive infections such as toxic shock or necrotizing fasciitis.

Vaccines: No vaccine is currently available for strep throat, though research is ongoing.

Scarlet Fever—Strep’s Rash Cousin

Before wrapping up strep throat, let’s talk about its rashy cousin, scarlet fever. Unlike strep throat, scarlet fever adds a rash that feels rough like sandpaper and a bright red tongue that peels. It’s the same bacteria behind strep, but not every strain produces the toxins that cause these extra symptoms—and not every child reacts to those toxins the same way. That’s why some kids exposed to strep only get a sore throat, while others break out with the classic rash and strawberry tongue.

Like strep, scarlet fever must be treated with the full course of antibiotics—not just to bring relief, but to prevent serious complications like rheumatic fever, which can threaten the heart and joints. In places like the UK, seasonal outbreaks still occur, so rapid treatment and full compliance remain crucial—no matter where in the world you live. My son had scarlet fever when he was seven, and that distinctive strawberry tongue and rash are hard to forget.

[*Image credit: Pp96, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons]

Transmission: Impetigo—commonly known as "school sores"—is a highly contagious bacterial skin infection that spreads via direct skin-to-skin contact or by touching contaminated objects like toys, towels, or linens. It’s especially common in warm, humid months and frequently occurs in young children attending daycare or school. The bacteria enter through broken skin—such as insect bites, eczema, or minor scratches.

Symptoms: There are two main types:

Non-bullous impetigo (most common): Begins as red sores often near the nose or mouth, which burst quickly, ooze fluid, and form honey-colored crusts. Fever is uncommon but nearby lymph nodes may swell.

Bullous impetigo: Features larger fluid-filled blisters (bullae), usually on the trunk, diaper area, or armpits—mostly in infants under age 2. These may rupture and leave thin brown crusts.

When to See the Doctor: Call your pediatrician if:

Sores cover a large area or are painful

They aren’t healing within a week

Your child develops fever or appears unusually ill

Signs of deeper infection (such as painful ulcers or spreading redness) occur.

Prevention:

Wash hands and clean minor skin injuries promptly.

Keep lesions covered and clothes, linens, and towels separate and clean daily.

Children can return to school at least 12–24 hours after starting antibiotics, as long as sores are covered.

Treatment:

Topical antibiotics such as mupirocin, fusidic acid, or ozenoxacin (newer option) are the first line for limited disease.

Oral antibiotics are used when lesions are extensive or for bullous forms (e.g., cephalexin, dicloxacillin). For MRSA coverage, options include clindamycin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Even untreated impetigo may resolve in a few weeks, but antibiotics shorten duration and reduce contagion.

Possible Complications:

Spread into deeper skin (cellulitis)

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (a kidney inflammation)

Rarely, acute rheumatic fever may follow skin infection.

Vaccines: No vaccine exists for impetigo. Prevention relies on early treatment, hygiene, and limiting spread.

Transmission: Mycoplasma pneumoniae spreads through respiratory droplets—when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks. Schools, where kids are in close quarters, are common settings for outbreaks. This organism lacks a cell wall, making it different from many bacteria and naturally resistant to antibiotics like penicillins.

Symptoms: Symptoms often appear gradually over days and include a persistent dry cough, low-grade fever, headache, fatigue, and sometimes shortness of breath. Because it unfolds slowly, kids can appear only mildly ill—hence the nickname “walking pneumonia.”

When to See the Doctor: Reach out if the cough lasts more than a week, doesn't improve, or is accompanied by trouble breathing, wheezing, or persistent fatigue. Given recent trends, considering M. pneumoniae as a cause early may help with timely diagnosis and treatment.

Prevention: There is no vaccine available. Prevention focuses on basic hygiene: handwashing, staying home when sick, and avoiding close contact during outbreaks.

Treatment: Antibiotics such as macrolides—like azithromycin—are the first-line treatment. These help shorten the illness and reduce transmission. Penicillins are ineffective due to the lack of a bacterial cell wall.

Possible Complications: Most cases are mild, but complications such as bronchitis or pneumonia can occur. Rare complications may involve the skin, blood, or nervous system.

Vaccines: There are currently no vaccines for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, though research continues.

Transmission: Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a highly contagious bacterial infection caused by Bordetella pertussis. It spreads through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks—making classrooms and schools ideal environments for transmission.

Symptoms: The early signs resemble a cold—runny nose, mild fever, and cough—that develop into severe, repeated coughing fits. These can end with a “whooping” sound when the child inhales or vomiting after coughing. Infants may show subtler signs, like apnea or color changes.

When to See the Doctor: Seek medical attention if a cough persists or worsens, especially if it's accompanied by vomiting, difficulty breathing, or that distinct whooping sound. Infants are particularly at risk and should be evaluated promptly.

Prevention: Vaccination is key. Children should receive DTaP shots starting at 2 months with booster shots as needed. Pregnant individuals should get Tdap during each pregnancy to protect newborns. Despite high coverage, immunity wanes, and outbreaks can occur when vaccination rates fall.

Treatment: When caught early, antibiotics like azithromycin or erythromycin shorten infectiousness and may lessen symptoms. However, once coughing has started, they do not stop symptoms immediately—they do help end the spread.

Possible Complications: Whooping cough can be serious—especially for infants. Complications include dehydration, pneumonia, seizures, apnea, ear infections, and in rare cases, death. Hospitalization is common in severe cases, with long-term effects like weight loss or broken ribs possible due to violent coughing.

Vaccines: Yes—vaccines exist and are highly effective. Acellular pertussis vaccines used today prevent about 85% of typical cases shortly after vaccination, though effectiveness wanes over time so you'll need a booster. They’re a critical tool for reducing whooping cough spread.

Global School Outbreaks: Beyond the U.S.

We’ve talked about the usual U.S. suspects—colds, flu, RSV, strep, norovirus. But if you’re listening from elsewhere in the world, the story can look a little different. Around the globe, schools are also hot spots for other infections worth mentioning.

Airborne Vaccine-Preventable Illnesses: Measles, Mumps & Meningitis: Let’s start with the airborne illnesses—measles, mumps, and meningitis—that still cause major school outbreaks worldwide.

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known—one case can infect 12 to 18 others if no one is immune. Outbreaks still occur in Europe, Africa, Asia and yes, as we've seen up close this year the US and Canada. Basically you get outbreaks whenever vaccination rates slip, and schools are often ground zero. Kids typically develop high fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes, and then the telltale rash. Because I’ve already done two full episodes on measles—one a deep dive into the disease and its vaccines, and another on the global measles situation in 2025—I’ll direct you there if you want more detail.

Mumps is a truly global infection and continues to resurface—often in high schools and colleges—because immunity from the combined MMR vaccine can fade over time; in fact, where measles cases rise due to vaccine gaps, mumps often follows, since protection against both depends on the same vaccine. Symptoms often begin mildly, with fever, headache, muscle aches, fatigue, and appetite loss a few days before the tell-tale parotitis—a tender, swollen jaw and “puffy cheeks” on one or both sides, due to inflammation of the salivary glands under the ears . This swelling usually lasts about five days and resolves within ten. In vaccinated individuals, symptoms are generally milder and complications less common—but they still do occur .

Complications, although uncommon, can be serious:

Orchitis—painful swelling of the testicles—that can happen in older boys and teens after puberty. It’s uncomfortable, and in rare cases it can affect fertility., occurring in about 30% of unvaccinated and 6% of vaccinated cases; may lead to testicular atrophy or reduced fertility.

Hearing loss—either temporary or permanent, especially in meningo‑encephalitic cases.

Less often, mumps can affect other parts of the body too. These complications can include swelling around the brain (meningitis or encephalitis), inflammation of the pancreas, ovaries, or breasts, or—more rarely—heart problems, paralysis, or seizures.

Death is exceedingly rare in both vaccinated and unvaccinated patients .

IMD: And then there’s invasive meningococcal disease (IMD), caused by Neisseria meningitidis. While less common than measles or mumps, it’s far more dangerous. It spreads through close contact—coughing, kissing, or sharing utensils—and can cause sudden fever, headache, stiff neck, sensitivity to light, and sometimes a purplish rash. It can lead to conditions like meningitis (brain and spinal cord inflammation) or sepsis (bloodstream infection), progresses rapidly and can be fatal within hours without urgent treatment. Schools, boarding environments, and especially college dorms are high-risk. Outbreaks also remain a major issue in Africa’s “meningitis belt.” For more detail, I have a separate episode dedicated entirely to this meningococcal disease.

The good news is all three illnesses—measles, mumps, and IMD—are vaccine-preventable. Keeping up with MMR and meningococcal vaccines is the best protection, and boosters may be needed for long-lasting immunity.

But—and this is important—when it comes to meningococcal disease, the vaccines that matter most depend on where you live. In the U.S., the routine shot on the schedule for middle and high schoolers is the MenACWY vaccine—that covers strains A, C, W, and Y. But here’s the catch: it doesn’t cover MenB, and MenB is the strain behind every meningococcal outbreak on U.S. college campuses since 2011. That’s why MenB vaccination is especially important for college students and military recruits—but you have to ask for it, because it’s not automatically included in the standard schedule. Globally, the picture looks different. In Africa’s meningitis belt, massive MenA campaigns have nearly wiped out that strain, but outbreaks from C, W, and X still occur, making multivalent vaccines like MenACWY critical. In Europe and parts of Latin America, MenB and MenC are big players, so many countries now vaccinate infants against them. And in places like Saudi Arabia, MenACWY is required for Hajj pilgrims to prevent devastating outbreaks. The bottom line: know which strains are most common where you are, and make sure your kids—and you—have the right protection.

Skin-to-Skin Spread: Scabies: You may not hear much about it in the U.S., but globally,

scabies is one of the most common skin conditions in school-age children. It's caused by a tiny mite called Sarcoptes scabiei that burrows into the skin, causing relentless itching—especially at night. You don’t get it from brief contact; it spreads through prolonged skin-to-skin contact like hugging, sleeping close, or sharing clothes or bedding. And because one female mite can lay lots of eggs, the itch can linger even after the mites are gone.

Globally, it’s estimated that over 200 million people are afflicted at any one time, with rates highest in hot, tropical regions and crowded living conditions—think parts of East and Southeast Asia, Oceania, and tropical Latin America. Children are especially affected in schools, boarding facilities, or refugee camps, where close contact is unavoidable.

It’s not life-threatening, but the intense scratching often breaks the skin, leading to painful bacterial infections like impetigo, which in turn can put children at risk for complications like kidney inflammation.

Treatment is straightforward but must be thorough. You apply a topical medication like permethrin cream from head to toe—or in some cases, your doctor may prescribe oral ivermectin. Everyone in the household (or anyone with close contact) needs treatment at the same time to avoid reinfection. Clothing, bedding, and towels used in the last few days should be washed in hot water—or sealed in a bag for a few days, since mites can only survive 2–3 days off skin.

Scabies isn’t often talked about, but in crowded or resource-limited settings it’s a real public health issue—one that can cause stigma and disrupt school attendance if not addressed quickly.

Food and Waterborne: Typhoid & Paratyphoid: In parts of South Asia and Sub‑Saharan Africa, typhoid and paratyphoid fever remain significant school-associated threats—especially in areas without reliable clean water or sanitation. For parents in the US, typhoid isn’t usually a concern in schools, but in parts of South Asia and Africa, it’s as familiar and disruptive as norovirus outbreaks are here. These illnesses are caused by Salmonella enterica serotypes Typhi and Paratyphi, and spread via the fecal‑oral route—often through contaminated food, water, or surfaces, or through contact with someone who may be an asymptomatic carrier.

Parents should watch for the telltale symptoms: prolonged high fever, abdominal pain, headache, loss of appetite, and sometimes a rash of flat, rose-colored spots. They may also experience nausea, constipation or diarrhea, and unusual fatigue.

Vaccines are available—including injectable Vi polysaccharide and oral live-attenuated (Ty21a) options—and are recommended in many countries. A newer typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV) has shown better effectiveness and longer-lasting immunity. However, vaccine access varies significantly, and they’re not universally available in all at-risk communities.

Perhaps most concerning, antibiotic resistance is on the rise, particularly to drugs like fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins—making treatment more complex in places like Pakistan and parts of India.

For families in affected regions, the best protection includes improving sanitation, drinking safe water, practicing good hand hygiene, and getting vaccinated when possible.

When is your child sick enough to need a doctor?

“When is your child sick enough to need a doctor? That’s one of the hardest calls for parents to make, and it’s even harder in the middle of the night when you’re exhausted and worried. The truth is, most childhood illnesses can be managed at home with rest, fluids, and comfort care. But there are times when symptoms are red flags that something more serious is going on.

I’ve put detailed charts in the blog post for this episode at InfectiousDose.com, so you don’t have to memorize all of this. The tables lay out symptoms and fever thresholds by age, plus clear guidance on when to call your pediatrician, when to head to the ER, and when it’s time to call 911. Think of them as your quick reference. And they are from the American Academy of Pediatrics website healthychildren.org. Here on the podcast, I’ll walk you through the highlights.

First, let’s talk about symptoms beyond fever. The big red flags are things like: trouble breathing, a new or spreading rash—especially one that’s purple or comes with fever—seizures, or a child who just isn’t acting right even after their fever comes down. Persistent vomiting, diarrhea, or refusing fluids can also be concerning because of dehydration. And if your child is unusually sleepy, weak, or hard to wake up, that’s a cue to seek medical help right away.

Now, about fevers specifically. Fevers can be scary, but not every fever means a trip to the doctor. What matters most is your child’s age, the exact temperature, and how long it lasts. For newborns under 3 months, any fever of 100.4°F (38° C) or higher is an emergency—those babies need to be seen immediately. Call your doctor right away—they’ll usually want to see your baby immediately, or they may send you straight to the emergency department depending on how your clinic handles newborns. For older infants and toddlers, call the doctor for persistent high fevers, unusual sleepiness, or dehydration. For school-aged kids, the fever itself is less important than how they’re acting—if they’re struggling to breathe, confused, or unusually weak, that’s when you need help.

I know how unnerving fevers can be. When my son had roseola, his fever shot up to 104F (40C)—it scared me half to death. But after one dose of ibuprofen, he was running around like nothing had happened. Roseola looks dramatic but usually isn’t dangerous. And I want to be clear—when I say a virus like roseola isn’t a major health risk, I’ll tell you that. And when I say something like measles or meningitis is a serious threat, that’s not fear-mongering—it’s the reality.

If you want the specifics—including exact fever thresholds for each age group and dose charts for acetaminophen and ibuprofen—you’ll find those in the blog post. That way, when you’re in the thick of it, you’ll have a guide to lean on instead of trying to remember all the details.

Symptom | What to Watch For | Action |

Not eating or drinking | Refusing all fluids, signs of dehydration (dry mouth, few wet diapers) | Call doctor |

Breathing problems | Breathing fast, using extra muscles to breathe, grunting, wheezing | Call doctor or go to ER if severe |

Cough or congestion | Lasts more than a week or worsens | Call doctor |

Rash | New, spreading, purple/red rash, or rash with fever | Call doctor or ER depending on severity |

Sleepiness, weakness, fatigue | Child unusually tired, hard to wake, low energy even after fever is reduced | Call doctor or ER if severe |

Acting sick even when fever is down | Doesn’t return to normal behavior, very cranky or clingy | Call doctor |

Vomiting/diarrhea | Repeated episodes, not keeping fluids down | Call doctor |

Seizures | Any seizure → | Call Doctor |

Lasts > 5 min or no quick recovery → Call 911 | Emergency if prolonged or repeated → Call 911 |

Fevers that need attention

Child’s Age | Fever Threshold | What to Do |

Under 3 months | ≥ 100.4°F (38°C) rectal | Call doctor immediately. If unavailable, go to ER. |

3–6 months | > 102°F (38.9°C) or any fever + unusual sleepiness, irritability, or feeding issues | Call doctor. |

6–24 months | > 102°F lasting > 24 hrs with no other symptoms | Call doctor. |

2+ years | > 104°F or fever > 3 days | Call doctor if child isn’t improving or is very uncomfortable. |

Any age | ≥ 105°F or not responding to medicine | Go to the ER. |

Any age | Fever + any of the following: | Go to the ER. |

• stiff neck | ||

• trouble breathing | ||

• purple rash | ||

• severe pain | ||

• confusion | ||

Any age | Seizure with fever lasting > 5 min, or child doesn’t wake up/recover quickly | Call 911. |

Any age | Fever + blue lips, difficulty breathing, or unconsciousness | Call 911. |

How to Take Your Child’s Temperature

One thing that can feel surprisingly stressful as a parent is figuring out if your child really has a fever—and that starts with knowing how to take their temperature correctly. It sounds simple, but in the middle of the night, with a cranky baby or a restless toddler, it can be daunting. There are different thermometers and methods depending on your child’s age—oral, ear, forehead, rectal—and each has its place. Getting it right matters, because the difference between 100.4 and 102 degrees can change whether you’re calling the doctor tonight or waiting until morning. Here's everything you need to know.

1. Thermometer Instructions by Child’s Age

For newborns and very young infants, rectal temperature is the gold standard. As children grow, less invasive methods like oral, temporal, or ear thermometers can work well—just make sure to use them correctly. Regular cleaning, proper technique, and using the right method for your child’s age will help ensure accurate and reliable readings every time.

Newborns and infants under 3 months: Use a digital rectal thermometer—this provides the most reliable reading. Insert gently about ½ inch for babies under 6 months, up to 1 inch for older infants. Apply a small amount of lubricant (like petroleum jelly), position your child on your lap or a firm surface, and stop immediately if resistance is felt. Hold in place until it beeps, then read the temperature.

Children 4 years and older: Oral measurement is appropriate. Wait at least 30 minutes if they've had hot or cold drinks. Place the thermometer under one side of the tongue toward the back, close their lips gently, and wait for the beep before reading.

Temporal (forehead) thermometer: Safe and easy for any age. Slide or swipe across the forehead per the device instructions to measure the heat from the temporal artery.

Ear (tympanic) thermometer: Suitable for children 6 months and older—not reliable for younger infants. To ensure accuracy, pull the ear back and, if over 1 year old, up; aim between the opposite eye and ear. Wait 15 minutes if your child was outside in cold weather.

2. Use and Care for Your Thermometer

Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions for your specific thermometer.

Clean the thermometer tip before and after use with soapy water or an alcohol swab.

Label your thermometers—especially important if you have separate ones for oral versus rectal use.

3. Tips & Cautions to Keep in Mind

Avoid using pacifier thermometers for infants and fever strips on the forehead—they’re less accurate and should only be used for quick checks.

Cold environments, blankets, or recent outdoor exposure can skew readings, especially in ear and forehead methods.

Always watch your child during the temperature check and never leave them unattended with a thermometer.

Acetaminophen & Ibuprofen Dosing

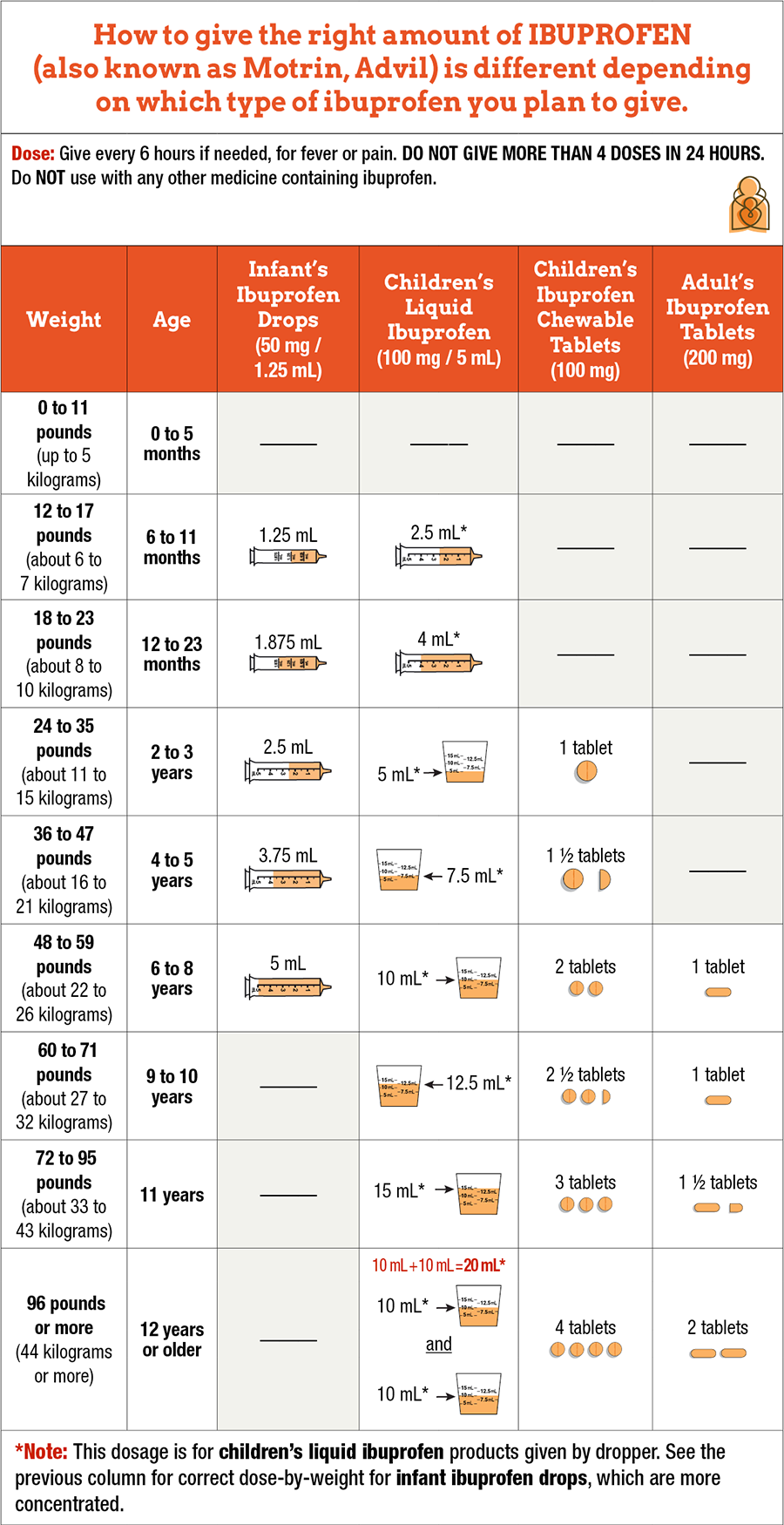

When it comes to helping your child feel more comfortable during a fever, two over-the-counter options are commonly used: acetaminophen and ibuprofen. Acetaminophen—often sold under brand names like Tylenol®, Feverall®, Tempra®, Actamin®, and Panadol®—is used to reduce fever and pain. Ibuprofen—known as Motrin® or Advil®—is also used to bring down fever and ease discomfort. Both are available without a prescription. One of the most common problems parents run into is giving the wrong amount of medicine, which is why using the correct dose for your child’s age and weight is so important. In the blog post for this episode, I’ve included acetaminophen and ibuprofen dosing charts from HealthyChildren.org, a website for parents run by the American Academy of Pediatrics. These charts make it simple to match

the right amount to your child’s weight or age—and you can always double-check with your pediatrician if you’re unsure. And let me clarify here that you should never give aspirin to kids because of the risk of Reye’s syndrome.

When to Keep Kids Home

So with all those germs swirling around, when should kids actually stay home? The general rule of thumb is fever—if your child has a temperature of 100.4 F (38C) or higher, they should be home until they’ve been fever-free for 24 hours without medicine. Vomiting or diarrhea are also clear keep-them-home signals, not only because the child is miserable but because they’re so contagious. A persistent, hacking cough, wheezing, or trouble breathing is another reason to stay home, both for the child’s sake and to avoid spreading whatever’s causing it. Pinkeye should usually mean staying home until it’s treated or improving, especially in younger grades where kids can’t keep their hands off their faces. And honestly, if your kid is just clearly not themselves—too tired to participate, lying down during class, unusually cranky—that’s a good enough reason to give them a rest day.

But here’s the catch: not every school district makes it easy for parents to keep sick kids home. In Tennessee, one district recently rolled out a policy that refused to excuse absences for illness—even with a doctor’s note—and threatened to send families to juvenile court after just eight missed days. After intense backlash, the district revised the policy. And that’s the lesson here: if your school board passes something this harmful, there’s no sneaking around it—teachers can’t bend the rules without risking their jobs. The only way forward is for parents to get involved. Show up at board meetings, talk to administrators, organize with other parents, and vote for leaders who protect kids’ health. In Lawrence County, Tennessee, parents pushed back—and they won. That kind of advocacy is how change happens.

Prevention

Let’s shift gears to prevention—what can you actually do to lower the odds of your child bringing home every virus under the sun? Some of it is classic advice: good old-fashioned handwashing really does help. Soap and water for 20 seconds beats hand sanitizer when hands are visibly dirty, but sanitizer is still a solid backup when kids can’t get to a sink. Teaching kids to cover their coughs and sneezes is another small but effective measure. And here’s the key—have them sneeze or cough into their elbow or shoulder, not their hands. Hands touch doorknobs, desks, and faces all day long, which is a recipe for spreading germs. Elbows and sleeves don’t touch surfaces as often, so that simple switch can make a real difference. Of course, most kids will sneeze straight into their neighbor’s face before they remember—but it’s worth teaching. Remind your kids not to share water bottles, snacks, or lip balm, even though sharing is encouraged in other contexts. And don’t skip those well visits—pediatricians often catch small issues before they snowball.

Masks

And here’s where I want to pause to talk about masks, because this is still a real issue in many places. Masks are one of the most effective tools we have for preventing the spread of respiratory viruses, but in the U.S. they became deeply politicized during the pandemic. In some schools, masks are welcome, in others they’re discouraged, and in some districts they’re even banned outright. That can be incredibly stressful if you’ve got a vulnerable family member at home—maybe someone on chemo, an immunocompromised child, or elderly grandparents who live with you.

My advice is to find out your school’s policy early, so you know what your options are. If masks aren’t allowed, you can lean harder on other protective measures like hand hygiene, flu and COVID vaccines, and good ventilation at home. And remember—masking doesn’t have to stop at the school doors. If your child comes home sick, parents can wear masks while caring for them to lower their own risk of getting infected. It’s even more effective if the sick child wears a mask, but let’s be real—that can be tough for younger kids to tolerate.

If masks are allowed at your child’s school, don’t let stigma stop you from using them. Parents and kids deserve to make the choices that keep their families safest.”

Vaccines

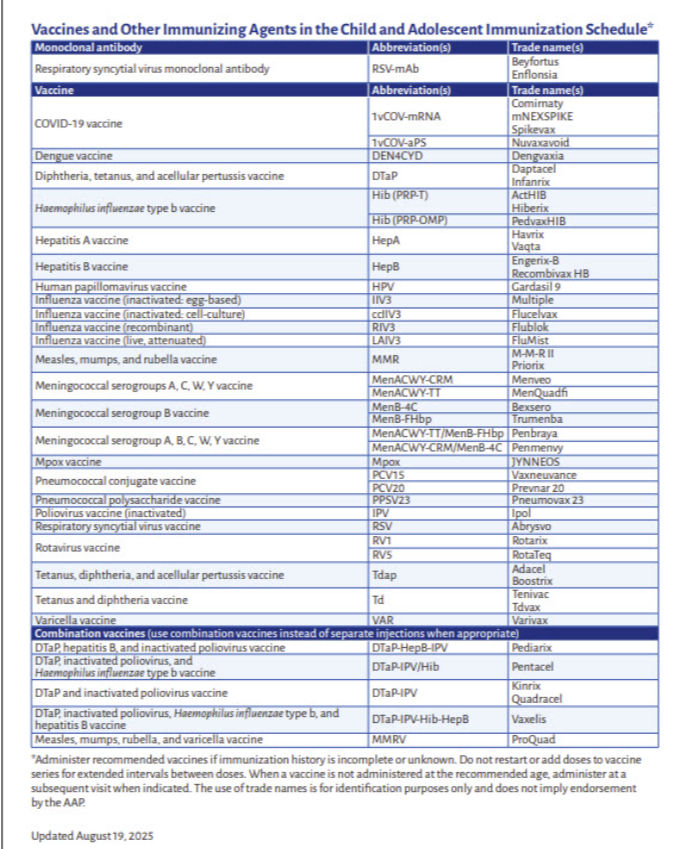

Vaccines are another powerful prevention tool. This isn’t a vaccine-centered episode, (I have a whole series on that) but it’s worth highlighting what’s on the recommended schedule for school-age kids. By kindergarten (ages 4–6), children should be up to date on DTaP, polio, MMR, and varicella, and will usually have completed the hepatitis B and hepatitis A series in early childhood. Annual flu vaccination is recommended for everyone 6 months and older. COVID-19 vaccination is still included on the American Academy of Pediatrics schedule for young children and teens, though the CDC now lists it under ‘shared clinical decision-making,’ meaning families can decide in consultation with their doctor. As kids get older, the HPV vaccine is recommended starting around 11–12 years, along with a Tdap booster at the same age, and meningococcal vaccines at 11–12 with a booster at 16. The point isn’t to overwhelm you with details but to remind you that vaccines aren’t just about checking a school requirement box—they protect your child and help reduce community spread of serious diseases.

Myth Busting

Before we wrap up, let’s do a quick myth-busting lightning round, because misinformation spreads as fast as viruses in schools.

Myth: Green snot always means infection. Not true. Green or yellow mucus is often just a sign your immune system is sending white blood cells to clean up a cold. But if that green snot lingers more than 10 days without getting better, suddenly worsens after improving, or comes with high fever, facial pain, swelling around the eyes, or a child who looks very unwell, that’s when it may point to a bacterial sinus infection—and that’s the time to call your doctor.

Myth: The flu shot can give you the flu. Nope. Flu shots are made from inactivated virus or viral proteins, which means they can’t cause infection. If you feel achy or run-down afterward, that’s actually your immune system building protection—a good thing. And remember, flu vaccination dramatically lowers the odds of severe illness, hospitalization, or complications.

Myth: Kids don’t really spread viruses. Oh yes, they do. Kids spread viruses very efficiently because they’re still learning good hygiene and spend so much time in close quarters. They’re also contagious before symptoms show. That’s why prevention—handwashing, cough etiquette, and staying home when sick—makes such a difference.

Myth: A cold is too minor to keep kids home. Not necessarily. Most colds are mild, but “just a cold” in one child can be much more serious for another. Kids with asthma, teachers with chronic conditions, or family members going through chemo can all be put at risk. Keeping a sick child home when possible isn’t just about your child’s recovery—it’s also about protecting the whole school community.

So here’s the takeaway. Back-to-school season is exciting, but it’s also germ season. You can’t prevent every illness, but you can reduce risk with simple steps, stay alert to the signs when your child needs to rest at home, and advocate for policies that support—not punish—parents trying to protect their kids and communities. If you’ve got questions, your pediatrician is always your best resource, but my website is a close second. Share this episode with a friend who’s stocking up on tissues and hand sanitizer right now—they’ll thank you when the first classroom bug hits. And remember, you’re doing your best in a tough season. Hang in there—you’ve got this.

Thanks for checking out the episode. Leave your questions in the comments or come find me on twitter or bluesky. Until next week, stay healthy, stay informed, and spread knowledge not diseases.

.png)

Comments