Dying of Thirst: Cholera in the Age of Abundance

- Heather McSharry, PhD

- Jul 29

- 17 min read

Summary

Dying of Thirst: Cholera in the Age of Abundance dives into one of the most underreported but devastating public health emergencies of our time. In 2025, cholera—a disease we know how to prevent and treat—is resurging across the globe. From Sudan’s displaced children to Angola’s overflowing hospitals and the flooded gold fields of the DRC, thousands are dying not because of medical mystery, but because of systemic neglect.

This episode brings you inside the crisis through real stories and expert insights. We’ll explore how climate change, armed conflict, and collapsing water systems have created the perfect conditions for cholera’s comeback—and how UNICEF, MSF, and frontline workers are racing to contain the outbreaks.

You’ll learn what cholera is, how it spreads, and why the global health system is failing.

Listen here or scroll down to read full episode. It’s not just about cholera—it’s about everything broken, and everything still possible.

Full Episode

A child cups their hands to drink from a plastic bucket. It’s warm. Murky. But it’s the only water she has. Several hours later, she clutches her stomach. She vomits. Then the diarrhea starts. Watery. Relentless. Her skin goes cold. Her lips go dry. Her mother runs for help, but the clinic is miles away—and already full.

By morning, she’s gone.

It started with a sip. One swallow of water—the very thing meant to keep her alive. This isn’t a war story. It’s cholera. And it’s back.

After years in retreat, it’s now surging across the globe—from Angola to Haiti, Sudan to Malawi—sickening hundreds of thousands and killing far too many. It’s ancient. It’s brutal. And it’s preventable. But right now, over a billion people are in its path.

This is Dying of Thirst: Cholera in the Age of Abundance.

How did we get here?

Well, a perfect storm of climate disasters, collapsing water systems, and neglected public health infrastructure has opened the floodgates. Droughts, floods, and armed conflicts have broken the most basic human shield against cholera: clean water and sanitation. Entire communities are now forced to rely on contaminated sources, while vaccines run short, and treatment supplies dwindle.

This episode isn’t just about understanding the science—it’s about understanding the stakes. Because every child dying from cholera today is a reminder that we have the tools to prevent this—but not yet the will.

What Is Cholera?

Cholera. The name might conjure up images of 19th-century pandemics or forgotten textbook pages. But to understand today’s crisis, we need to go back to basics: what exactly is cholera?

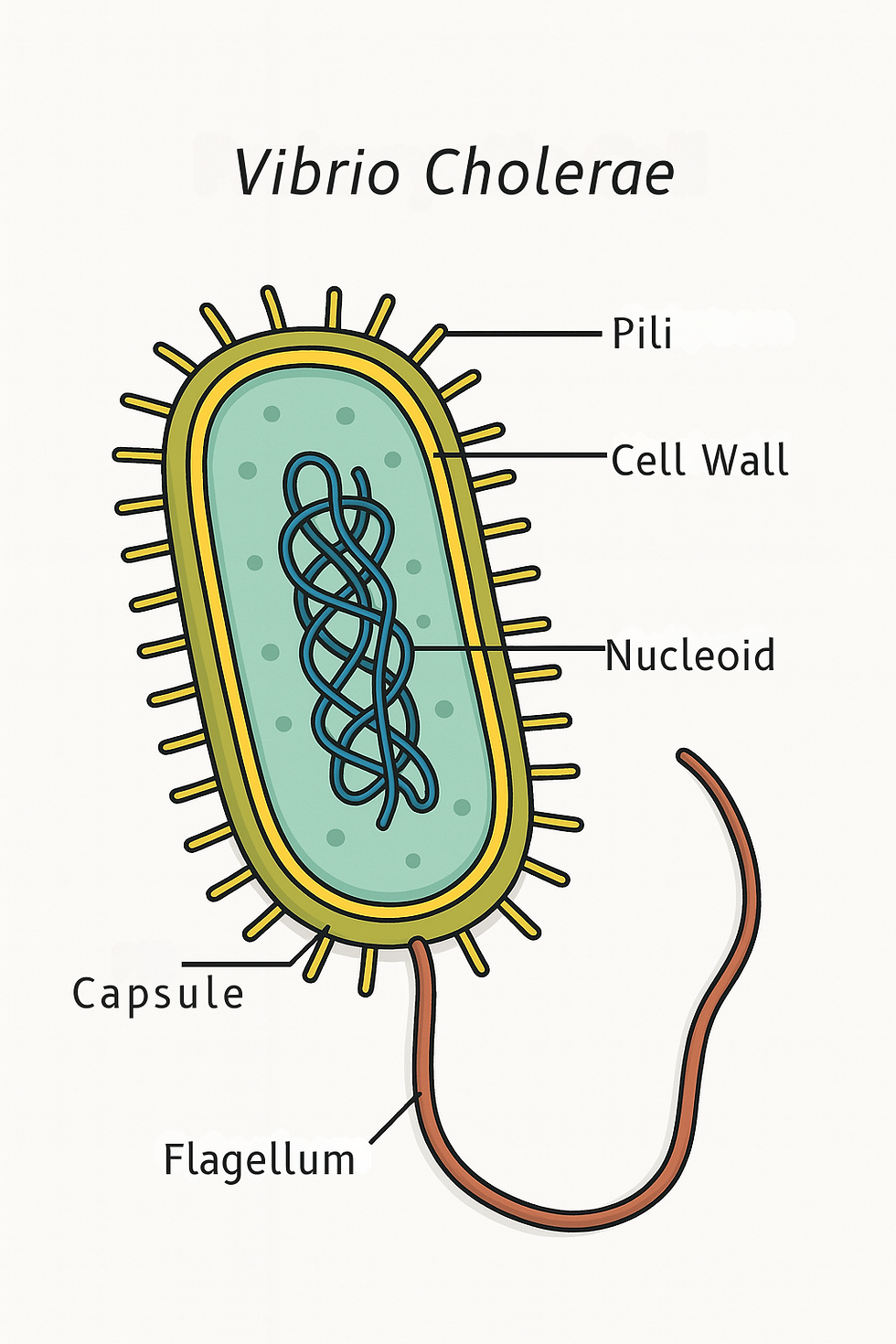

Vibrio cholerae is a highly motile, comma-shaped bacterium equipped with a single polar flagellum—a built-in propeller that lets it swim through water and mucus with ease. It's a natural inhabitant of aquatic environments worldwide.

More than 200 serogroups of V. cholerae have been identified. These groups are classified based on variations in the O-antigen structure of a molecule on the bacterial surface called lipopolysaccharide, or LPS. If you want to know more about LPs check out my episode on invasive meningococcal disease Close Quarters, Silent Threat, I have a whole sidebar on LPS in that episode. OK, so anyway, most of the 200 cholera serogroups are harmless or only cause mild illness. But two stand apart.

Only serogroups O1 and O139 carry the genetic arsenal needed to produce cholera toxin (CTX)—the protein responsible for the explosive, dehydrating diarrhea that defines cholera. These strains are the ones behind major outbreaks and global epidemics. The rest—called non-O1/non-O139 strains—don’t produce cholera toxin. They may cause minor gastrointestinal infections, isolated cases of bloodstream infection, or wound infections, but they do not cause epidemic cholera. And even among O1 strains, there’s more to the story.

O1 strains are further divided into three serotypes: Ogawa, Inaba, and the much rarer Hikojima. These classifications depend on whether the terminal sugar on the LPS—called perosamine—is methylated.

Ogawa strains are methylated,

Inaba strains are unmethylated,

and Hikojima strains express both forms.

Interestingly, Ogawa and Inaba strains can switch between serotypes, a kind of microbial shape-shifting that allows them to evade host immunity during outbreaks. Hikojima is believed to be a rare, unstable transitional form—a stepping stone during serotype switching, rather than a stable identity.

Another important classification is biotype. The O1 strains come in two biotypes: Classical and El Tor. These can be distinguished by genetic and phenotypic traits—and they behave differently in the real world.

Classical strains tend to cause more severe disease but don’t persist as well in the environment.

El Tor strains, on the other hand, are hardier: they survive longer in water and in the human gut, spread more easily between people, and are more likely to infect without causing symptoms—creating stealthy, asymptomatic carriers.

So while Vibrio cholerae may be widespread, it’s only a small, specific group of strains—armed with the right genes and traits—that pose the real threat. And understanding exactly which strain you're dealing with can help predict how it spreads, how severe it is, and how best to stop it.

Pathogenesis

Once ingested—usually through contaminated water or food—Vibrio cholerae begins a journey of survival and sabotage. The incubation period of cholera can range from several hours to 5 days. First, it must pass through the acidic gauntlet of the stomach. Toxigenic strains have an acid tolerance response that helps them survive this hostile environment.

In the small intestine, the bacteria use their flagellum to propel through the protective mucus layer and reach the intestinal surface. But even there, they face stiff competition from the resident microbiota and the immune system. To colonize, V. cholerae unleashes a toolkit of virulence factors.

One of the most critical is the toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP)—a kind of molecular grappling hook that helps the bacteria anchor to the intestinal lining. Once attached, it releases that weapon we learned about a minute ago: cholera toxin or CTX. CTX doesn’t tear through tissues or trigger inflammation. Instead, it hijacks the gut’s cellular messaging system. It flips on a signaling molecule called cAMP, which throws off the body’s fluid balance—causing massive secretion of electrolytes like sodium, chloride, bicarbonate, and potassium into the intestinal tract. Water follows in a torrent.

The result? Profuse, high-volume diarrhea that’s often described as “rice water stools”—clear, cloudy liquid speckled with mucus. Vomiting is also common. And in severe cases, the body can lose gallons of fluid in a matter of hours. This rapid dehydration can trigger hypovolemic shock—when the body loses so much fluid that there’s not enough blood to circulate—causing the organs to fail, the kidneys to shut down, and death to come quickly if rehydration isn’t immediate.

And here’s an interesting twist: Vibrio cholerae doesn’t invade tissues. It’s what we call a noninvasive pathogen. That means it doesn’t burrow into cells or spread through the bloodstream like many other deadly bacteria. Instead, it stays on the surface of the gut, anchoring itself to the intestinal lining and unleashing biochemical chaos from the outside. The real damage comes not from the microbe itself, but from the toxin it secretes—a molecular saboteur that hijacks the body’s own signaling systems, turning the intestine into a high-volume drainpipe.

Other virulence factors—like HapA, GbpA, and NanH—support the process by breaking down mucus, enhancing adhesion, or scavenging nutrients, but the real damage is done by the toxin alone.

So in the end, cholera doesn’t kill with brute force. It kills by flipping the gut into a self-draining faucet—quietly, quickly, and catastrophically.

Epidemiology and Transmission

Cholera is transmitted via the fecal-oral route, thriving in areas with unsafe water, poor sanitation, and fragile healthcare systems—especially in the wake of conflict, disaster, or displacement. You might remember this is the same as polio I talked about a few weeks ago. There's a pattern here, yeah? Taking care of our communities with basic necessities will wipe out transmission of many diseases. OK, so The World Health Organization estimates that 1.4 to 4 million cases of cholera occur annually, causing up to 143,000 deaths. Underreporting is widespread due to limited diagnostics, lack of surveillance, and stigma.

While historically endemic in South Asia, cholera is now entrenched in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and parts of the Middle East. The current, seventh global pandemic began in 1961 and continues to evolve, with the El Tor strain of V. cholerae O1 dominating the global landscape.

Ecology and Evolution

Ecologically, V. cholerae is a waterborne organism. It naturally lives in coastal and brackish waters and can persist in aquatic environments for extended periods. Human and animal waste amplify its spread. V. cholerae shed in rice-water stool remain hyperinfectious for a few hours—one reason outbreaks can explode so quickly. Being hyperinfectious means the bacteria become supercharged—they're more contagious, more efficient at infecting the next person, and far more likely to cause new cases of cholera.

These hyperinfectious bacteria are still flagellated and highly motile—basically, they’re swimming machines—but they temporarily dial down many of their usual virulence genes, including the ones responsible for producing cholera toxin and helping them latch onto the gut. We don’t yet fully understand how this state is triggered, but we know it doesn’t last long—just a few hours after being shed.

Why does this matter? Because it means that rapid person-to-person transmission—especially in places without proper sanitation—can drive outbreaks even faster than environmental exposure alone. In short, the fresher the stool, the higher the risk.

So when we talk about cholera spreading fast, it’s not just a matter of contaminated water—it’s also about timing, proximity, and this strange, fleeting state of hyperinfectious power.

And here’s something that often flies under the radar: people who carry cholera without showing any symptoms—what we call asymptomatic carriers—can still spread the disease. They typically shed the bacteria for only a short time, but even that brief window is enough to keep cholera circulating in a community. These silent carriers may feel fine, but they play a surprisingly important role in how the disease persists and spreads—especially in areas without safe water or sanitation.

Now, the evolution of cholera is fascinating. Over time, cholera has become deadlier—not by accident, but by inheritance. Strains like the notorious O139 Bengal variant have picked up powerful genetic tools from other microbes—bits of DNA that supercharge their ability to cause disease and resist treatment. We call these borrowed blueprints ‘mobile genetic elements’ or MGEs—and they’ve radically changed the game. To really understand what these guys do, let's have a sidebar on MGEs.

Sidebar: Mobile Genetic Elements — Borrowed Weapons in the Microbial World

MGEs are a kind of microbial “cut-and-paste” system. Think of them as biological flash drives: packets of DNA that can jump within a cell’s genome or move between completely different bacteria. MGEs are nature’s way of fast-tracking evolution.

Some of these elements work inside a single cell. Transposons—often called “jumping genes”—can hop from the bacterial chromosome onto a plasmid, or from one plasmid to another. Insertion sequences do something similar, often dragging along resistance genes like stowaways. Integrons specialize in swapping out gene “cassettes” at designated sites, almost like a USB hub.

But MGEs also move between bacteria—and that’s where things get really wild. Some bacteria transfer plasmids through a process called conjugation, like passing a note from one cell to another. Others share DNA through transduction, where viruses (like bacteriophages) serve as genetic couriers. Still others absorb free-floating DNA from their environment through transformation—literally taking in genetic fragments from dead neighbors.

And these elements don’t act alone. They often work together—hopping, swapping, and integrating in a dynamic network of genetic exchange. One MGE might cut a resistance gene out of a chromosome, another carries it into a plasmid, and a third delivers it to a new cell entirely.

It’s not slow mutation. It’s horizontal gene transfer—rapid, targeted upgrades in the microbial world.

This is exactly what happened with cholera. A virus called CTX phage infected Vibrio cholerae and left behind the ctxAB genes, which produce cholera toxin—the brutal molecule behind the life-threatening diarrhea. Other mobile elements followed, like VPI-1 (which enables intestinal attachment), and ToxT, a regulatory gene that flips the whole system on like a switch.

Together, these borrowed genes turned a harmless aquatic microbe into a powerhouse pathogen.

MGEs aren’t just a cholera story—they’re a global public health story. They’re behind antibiotic resistance in hospitals, superbugs in livestock, and deadly outbreaks in the wake of disaster. They are evolution on fast-forward—and they’re rewriting the rules of infection.

All right, let's get back to the episode.

Humanizing the Crisis

OK, you’ve just heard how the bacterium works—how it robs the body of fluid until there’s nothing left to give. But numbers and molecules can’t capture what that actually feels like. To understand the true cost of cholera, you have to step into the homes it empties. Into the clinics that run out of space. Into the silence that follows a child’s final breath. Because this disease doesn’t just move through intestines—it moves through lives. And when it strikes, it can be devastating.

Let’s begin in Khartoum, Sudan, where cholera returned with deadly force this May. In just one week, over 170 people died, and more than 2,500 were sickened. But this was no ordinary outbreak—it struck a city already broken by war. After two years of brutal conflict, many families had only just returned, hoping to rebuild. Instead, they found shattered water systems, collapsed sanitation, and an overwhelmed health infrastructure.

Joyce Bakker of Doctors Without Borders described the grim reality:

“Many patients are arriving too late to be saved … We don’t know the true scale of the outbreak, and our teams can only see a fraction of the full picture.”

Cholera didn’t stop at the city’s edge. It spread beyond the capital into provinces like North Kordofan, Sennar, Gazira, and White Nile—regions where clinics are few and resources fewer.

Why now? Why here? Because families, displaced by war, returned home, only to find their taps dry and their rivers fouled. One health worker emphasized the need for more than medicine. Without clean water and sanitation, medicine can only do so much.

In these moments, time becomes a weapon. Parents watch their children lose color by the hour. Bodies dehydrate faster than wheels can turn. The disease kills not just by biology—but by delay.

And yet, even in this grief, something else took root.

Volunteers dug open forgotten wells. Mothers carried water from block to block, risking their own health to spare others. One father—who had already buried a daughter—stayed up through the nights, knocking on doors, warning neighbors to boil water and avoid raw food. The pain was personal, but the mission became communal.

Thousands of miles away, in Bairro Paraíso (BY-hoo pah-rah-EE-zoo), Angola, cholera arrived with similar cruelty. And yet, three women—survivors and witnesses—chose to resist.

Juliana Manuel Bravo, a 39-year-old cleaner, watched a neighbor’s children die despite her efforts. Then, her own four children fell ill.

“At my house there were 5 people with the same symptom. I was the first person, then my 19-year-old son, then the 24-year-old, then the 14-year-old and 9-year-old. My husband was the one who was up and down with us.”

Ana Maria, 26, lost her young son on January 6.

“...no one knew it was cholera because it was starting. They took him to the hospital at my sister's, but he died the same day.” Days later, when her sister began to vomit, Ana knew—and acted.

Domingas Manuel Joaquim, 31, had survived cholera once before. So when her son grew weak and dehydrated, she didn’t hesitate.

“In my house, my son was the one who caught cholera. As I already knew, I went to the pharmacy, bought serum, gave it, but it wasn't going through. Someone advised me to take him to the FAS, because that's where they were treating these cases.”

Today, these women are not just survivors—they’re educators. They teach, warn, and guide—not with degrees, but with experience. With memory.

Juliana: “We have to be more careful with garbage. Because cholera really kills. We lost neighbors, children, grandchildren.” Ana: “Let's take good care of our bathrooms, treat water before drinking, take care of food, and prevent our children from defecating in the open, because that's exactly where this disease is coming from.”

And hey, it may sound basic to those with indoor plumbing, but in places without toilets or water systems, this is the daily reality—not because people don’t know better, but because they’ve been left without options.

And the truth is, from Khartoum to Paraíso, the message is clear: Cholera thrives where systems fail. But it dies where communities rise. These voices remind us: the cure doesn’t only come in IV bags. It comes in knowledge. In vigilance. In love. And these aren’t isolated tragedies. They’re signals—of a storm spreading across continents.

Let’s pause here and talk about something rare in cholera: survival.

So, what does treating cholera successfully involve? Well, when it comes to cholera, time is everything. The number one priority isn’t antibiotics—it’s rehydration. Patients can lose liters of fluid in just hours, and the key to survival is replacing those fluids fast, using oral rehydration salts (ORS). About 80% of cholera patients experience mild or no symptoms and can recover fully with oral rehydration salts (ORS) alone. For those with severe dehydration, intravenous fluids—specifically Ringer’s lactate—are essential. When administered correctly, rehydration can reduce case fatality rates from 50% to under 1%.

And you can make your own ORS at home! This PDF from the University of Virginia Health System has several recipes for ORS including the one in the infographic.

What about antibiotics? They help—but they’re not the frontline treatment.

Antibiotics can shorten the duration of diarrhea by more than a day, reduce stool volume by 50%, and decrease the amount of ORS needed. They also cut the period of vibrio shedding—which helps curb transmission. But here’s the catch: they’re not for everyone. According to current global guidelines, antibiotics are reserved for:

Patients with severe dehydration,

Patients with high purging (e.g., one stool or more per hour in the first 4 hours),

Those with treatment failure (still dehydrated after initial rehydration), and

Individuals with comorbidities or vulnerable conditions like malnutrition, HIV, or pregnancy.

When antibiotics are needed, doxycycline is the first-line choice for most patients—including pregnant women—administered as a single dose (300 mg for adults, 2–4 mg/kg for children). If resistance is a concern, alternatives include azithromycin or ciprofloxacin. But no matter the drug, it’s started only after vomiting has stopped, to ensure it stays down and does its job.

In children aged 6 months to 5 years, zinc supplementation is also recommended regardless of the severity of dehydration. A daily 20 mg dose of zinc for 10 days can reduce the volume and duration of diarrhea significantly. However, zinc may interfere with the absorption of some antibiotics, so it’s best administered either 2 hours before or 4–6 hours after the antibiotic.

Pregnant women with cholera need close monitoring. Dehydration during pregnancy is especially dangerous, significantly increasing the risk of fetal loss. For them, even mild symptoms call for aggressive rehydration, continuous blood pressure checks, and prompt antibiotic treatment.

In short: unlike for most bacterial infections, cholera treatment is a race against dehydration. Rehydration wins that race. Antibiotics help close it out. Together—with zinc in young children and attentive care for vulnerable patients—they can turn the tide against cholera.

Now let's move into how cholera is sweeping the globe in 2025. Around the world, cholera is resurging with a vengeance—tearing through towns and refugee camps, thriving on conflict, climate disaster, and broken systems. Let's go into the heart of the crisis—country by country—to see not only how cholera is spreading, but how courage is rising with it. I’ll walk you through some for which I could find information, though it's not a complete list. For all countries affected by cholera, check out the WHO cholera dashboard. Here's a screenshot.

And here's the most recent WHO Cholera sitrep in case you're interested:

Let's start with Angola

Angola: Epidemic on the Edge. Since January 2025, Angola has reported over 15,800 cholera cases and more than 500 deaths. One-third of those deaths didn’t happen in hospitals—they happened at home. In the streets. In silence. The disease is moving fast—sweeping across 17 of the country’s 21 provinces. And with the rainy season in full swing, the overwhelmed sanitation systems aren’t stopping cholera. They’re accelerating it.

But Angola is fighting back. The government launched two rounds of emergency vaccination, reaching more than 1.6 million people. WHO and UNICEF rushed in with treatment centers, water tanks, and hygiene kits for schoolchildren. Still, it’s a race against time—and the virus is ahead.

Sudan: Water as a Weapon. In Sudan, cholera has collided with war. Since January, over 32,000 people have been infected, and more than 700 have died. Bombed water facilities have left neighborhoods with no clean water. In some clinics, patients die not from disease—but from the absence of IV fluids. Into this vacuum stepped frontliners.

The International Medical Corps opened rehydration centers in war zones. UNICEF distributed more than 7.6 million vaccine doses. And mobile teams crossed dangerous terrain to reach the sick. But the crisis is massive—and growing faster than the response.

South Sudan: Hidden Toll. Nearly 39,000 people have fallen ill this year. Almost 750 have died. But in South Sudan, the full extent of the outbreak remains unknown. Insecurity and collapsed health surveillance mean most cases simply aren’t counted. The virus is moving in the dark—and so is much of the suffering.

Democratic Republic of Congo: Cholera in the Gold Rush. In the hills of South Kivu, a gold discovery drew thousands. Makeshift settlements popped up overnight—no toilets, no water systems. Cholera exploded. In just two weeks, cases surged by 700%. Lomera alone accounted for nearly all regional infections. MSF moved fast. They vaccinated 8,000 people in four days. They built clinics where there were none. In the jungles of Walikale, teams carried oral rehydration salts through bush paths—saving lives with nothing but grit and determination.

Malawi: Floods and a Fight for Life. In Malawi, the rains didn’t just bring water—they brought death. Flooded villages became breeding grounds. Hospitals overflowed. Cholera patients arrived too late, too often. So health workers adapted. They handed out ORS at bus stops. They brought water tanks into schools. They didn’t wait for perfect systems—they improvised. And it worked.

Haiti: Hope Amid Crisis. Years of crisis weakened Haiti’s defenses. But when cholera struck, communities struck back. Nurses set up handwashing stations in churches. Volunteers distributed clean water door to door. Emergency vaccine shipments arrived just in time. In a country battered by disaster, hope held.

Nigeria: Racing the Outbreak. Across 13 Nigerian states, cholera is moving fast—3,500 cases and climbing. Overflowing latrines in displacement camps. Dirty water. Seasonal floods. Health teams are trying to keep up. Mobile units. Hygiene radio campaigns. But, as one official said:

“We are racing cholera—and it’s faster than we are.”

Cameroon: A Silent Strain. Cameroon’s outbreak doesn’t make headlines—but it’s deadly. Over 4,600 infected. 110 lives lost. No toilets. No clean water. No voice. UNICEF is responding—with hygiene kits, clean water tablets, and public education. But the healthcare system is cracking.

Of course, the countries we've covered here are just part of the story. Cholera is surging across dozens of regions this year, and we can’t detail them all. But it’s important to note that significant outbreaks are also unfolding in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh (especially among displaced populations in Cox’s Bazar), Thailand, Myanmar, and Yemen, where fragile health systems, displacement, and conflict have fueled rapid spread. Some of these outbreaks are reported as “acute watery diarrhea,” but they’re tracked alongside cholera because the conditions—and the consequences—are just as dire. The global map of cholera in 2025 spans continents, but the pattern is painfully familiar: where water fails, cholera follows.

Global Coordination, Local Action

From Angola to Cameroon, cholera is showing us two things at once:

That our systems are fragile. And that our people are fierce. Agencies like UNICEF, WHO, and MSF are deploying vaccines, building clinics, and training frontline health workers. But the most powerful work? It’s not the labs. It’s the locals. It’s those installing water tanks, teaching children to wash their hands, and rushing to carry a neighbor to safety.

And here's the thing, we have the opportunity here to act before it’s too late. Because cholera is preventable. But how?

Prevention and Control

Well, prevention hinges on one word: WASH—which, in this case, is an acronym for water, sanitation, and hygiene.

Because cholera spreads through contaminated water and food, the most powerful defense is clean infrastructure. That means safe drinking water, proper sewage systems, and the ability to wash hands, clean surfaces, and store food safely. It’s basic—but in many communities, it’s still out of reach.

Alongside WASH, there's another crucial layer of protection: oral cholera vaccines, or OCVs. These vaccines don’t provide lifelong immunity, but they are highly effective for outbreak control and essential in places where cholera is endemic. Unfortunately, the global supply is dangerously low right now—making prevention more urgent than ever.

But stopping cholera isn't just about pipes and prophylactics. It’s also about speed and strategy. Rapid diagnostic tests help identify outbreaks fast, and immediate treatment prevents deadly dehydration. But that treatment depends on strong health systems—trained health workers, labs that can confirm cases, and a steady supply of lifesaving tools.

Health education is just as critical. People need to know how to store food safely, treat their drinking water, wash their hands, and recognize symptoms early. Public messaging through schools, churches, radio, and local leaders can make the difference between prevention and outbreak.

There’s also a growing threat behind the scenes: antibiotic resistance. In severe cases, cholera is treated with antibiotics—but some strains are becoming resistant. That’s why AMR surveillance is so important: to make sure we’re using the right drugs, and not making the problem worse.

Finally, we can’t forget the big picture. Cholera is a global health issue. International organizations like WHO, UNICEF, and Doctors Without Borders are coordinating responses and guiding long-term strategy. But no single country can solve this alone. The fight against cholera depends on global cooperation—because diseases don’t stop at borders.

And here's the truth: we won't eliminate Vibrio cholerae. It lives naturally in rivers, estuaries, and coastal waters. But we can eliminate cholera as a deadly disease—if we stop the conditions that let it thrive: poor infrastructure, slow response, and systemic neglect.

📢 Here’s What You Can Do

But this crisis isn’t abstract—and your action matters.

✅ Support frontline organizations like MSF, WaterAid, or UNICEF working in cholera-affected areas right now.

✅ Share this episode. Use your voice to raise awareness—because silence enables suffering.

✅ Call on governments to invest in WASH systems—not as charity, but as justice. Safe water is a human right, not a luxury.

And remember…

Cholera is preventable. Every death from it is a failure — not of medicine, but of will. As UNICEF puts it: ‘Cholera’s upsurge is an urgent wake-up call for us to act together and act now.’ The question is not whether we can afford to act—but whether we can afford not to.

Thank you for being here. And if you found this episode useful, share it with a friend, subscribe, or leave a review. Until next time, stay healthy, stay informed, and spread knowledge not diseases.

.png)

Comments