Outbreak After Dark 1. Ocularium: Four True Tales of Eye Horror

- Heather McSharry, PhD

- Oct 28

- 17 min read

Updated: Nov 4

Summary

🎃 Outbreak After Dark debuts with a Halloween special that peers into the world of eye-invading parasites—real creatures that crawl, swim, or dissolve their way into the human eye. Join Heather and her “partners in creep,” Kate and Sam, around the crackling campfire as they share four true tales of ocular infection: the wandering Loa loa worm, the blinding Onchocerca volvulus, the eye-eating amoeba Acanthamoeba, and the goat-yoga-gone-wrong eyeworm Thelazia gulosa. It’s science you can’t unhear—equal parts fascinating, horrifying, and disturbingly real. Pull up a chair by the fire, grab your Parasight Cider or Don’t Blink S’mores, and learn why sometimes… it’s not just superstition that makes you afraid to open your eyes.

Listen here or scroll down to read full episode.

Full Episode

Heather: “There’s something in your eye… and it’s looking back.”

Welcome to Outbreak After Dark, a new monthly ritual here on Infectious Dose. It’s still me, Heather — your resident virologist and science communicator — but tonight, we’re stepping just a little further into the shadows. This is where the science stays real, but the stories get darker, weirder, and yes... sometimes just plain gross.

We’re calling it Outbreak After Dark because that’s when the whispers start, the campfire crackles, and the line between infection and urban legend begins to blur.

Bubble, bubble, germs that double…

Parasites creep, infections trouble.

Eyes that wander, worms that bite…

Outbreak After Dark, this Halloween night.

Heather: And I’m not alone for these after-dark tales. Joining me around the fire are my two favorite partners in creep:

Heather: Kate — a wickedly witty librarian who can fact-check your ghost story while she’s telling you one… even if she’d really prefer not to hear it at all.

Kate: Perfect. I’m the person who hates scary stuff… and somehow I still got invited to scary story night.

Heather: And Sam — a former teacher turned tech wizard, who loves a good scare almost as much as I do.

Sam: See, I came prepared. Flashlight, cider… and zero regrets.

Heather: Excellent. Every Outbreak After Dark will follow the same ritual: a fire at our side, snacks and cocktails that match the theme, and true infectious disease stories that you can’t unhear — no matter how hard you try.

Kate: Tonight’s menu is disturbingly on-brand — even for us.

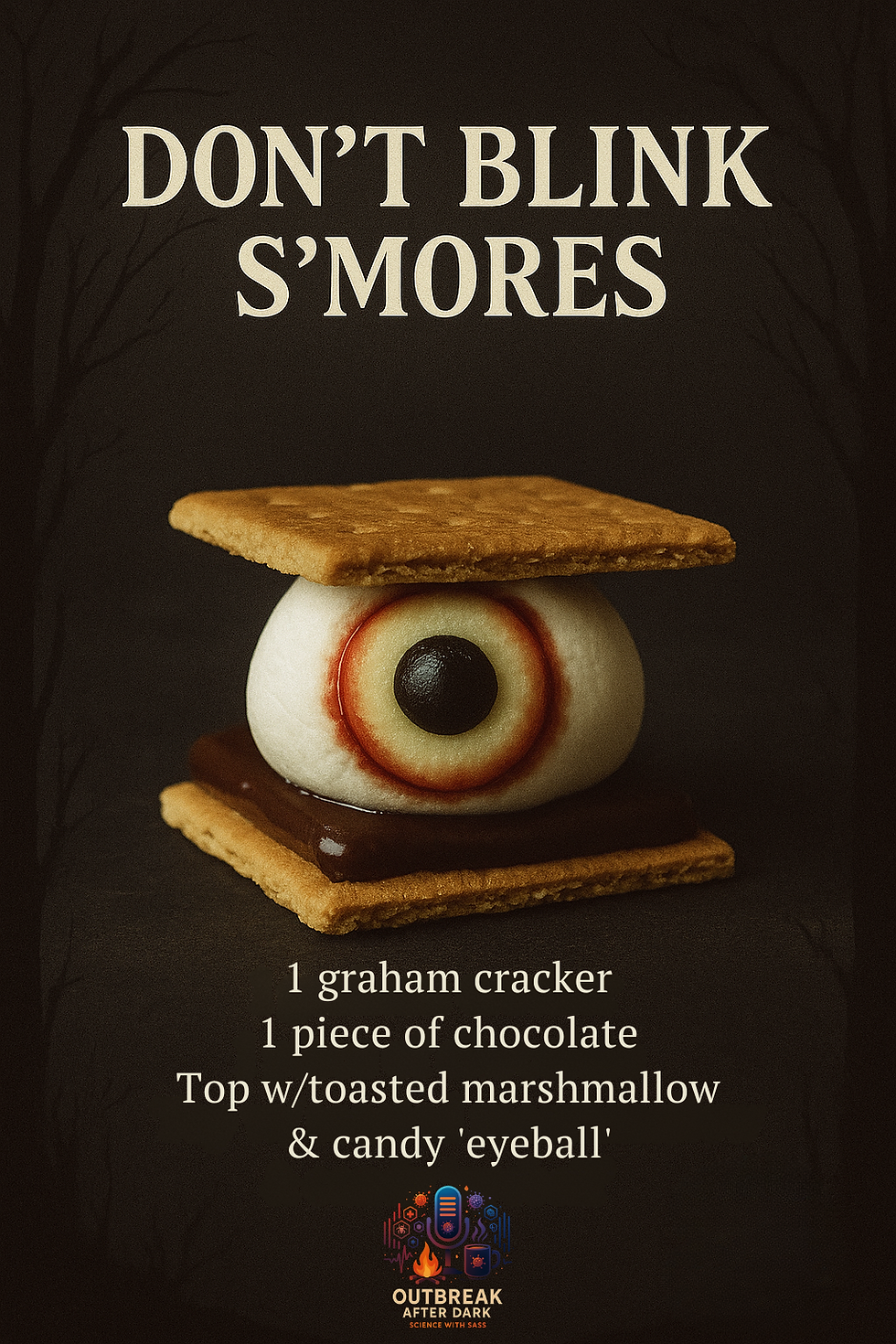

Heather: Yes, we’ve got Deviled Eyes — protein-packed and unsettling...Don’t Blink S’mores — complete with marshmallow eyeballs that watch you melt……and steaming mugs of Parasight Cider, topped with caramel, whipped cream, and a floating eye that definitely wasn’t FDA-approved.

Sam: I’m just saying, if mine blinks, I’m throwing it in the fire.

Heather: Listeners — if you want to eat and drink along with us, you can find all the recipes in the blog post at InfectiousDose.com. But for now…

Snacks? Check. Drinks? Check. Flashlights? Optional.

Kate: Nightmares? Pending.

Sam: Therapy fund? Growing.

Heather: Then let the ritual begin.

All together: This is Outbreak After Dark.

Heather: Because tonight’s stories? They don’t just stare back. They live inside your eyes.

Loa Loa: The Eye Wanderer

Heather: They say the eyes are the windows to the soul…But sometimes… something else gets in first.

This first story takes us to the forests of Central Africa — think

Cameroon, Gabon, the Congo. It starts with a woman who had nothing more than itchy, red eyes. Her doctors thought it was allergies. Maybe dust. Maybe dry season irritation.

Sam: Probably gave her some eye drops and sent her home?

Heather: Right? But then she felt something… moving. Not in her imagination. Not a twitch or a flutter. Something alive. And when she looked in the mirror, she saw it — a pale little worm, slithering right across her eyeball.

Kate: Oh no. Nope. Nope. Shut it down. I’m out.

Sam: Blink. Blink. Blink. Blink.

Heather: This is: Loa Loa — The Eye Wanderer.

Heather: So here’s how this works. Out there in the rainforest, deerflies buzz through the humid air — big, biting flies. One lands on you, takes a bite, and leaves behind something small. Microscopic. You wouldn’t notice it.

Kate: A gift. How thoughtful.

Heather: That “gift” is a larva — the immature form of a parasitic worm called Loa loa. Once it gets inside, it slips into your bloodstream and travels through your body. It takes months — even up to a year — to mature, and when it does, it just... starts wandering.

Sam: Through your blood?

Heather: Through your blood and under your skin. That’s where it lives — just beneath the surface. People feel it crawling across their face, their arms… and every once in a while, it decides to make a guest appearance across the eye.

Kate: I am never touching my eyeballs again.

Heather: You touch your eyeballs?

Kate: You know what I mean.

Sam: Wait, how long does this thing stay in your body?

Heather: It can live for up to 15 to 17 years. Yep. Just hanging out under your skin.

Sam: That’s not a worm. That’s a tenant.

Kate: That's a tax dependent. So is this, like… rare? Or is this happening all the time and we just don’t talk about it?

Heather: It’s common in parts of Central and West Africa — mostly in the rainforest regions where the deerflies live. But with climate change shifting habitats, there’s concern it could expand its range. And there have been occasional imported cases — people who travel and come home with more than just souvenirs.

Sam: OK, with this being Halloween, I cannot say Loa Loa without saying it to the tune of the Twilight song. You’re saying Loa loa could move?

Heather: If the flies move, the parasite moves. Warmer temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns change where those flies can survive.

Kate: Okay, but what do people actually feel when they’ve got it?

Heather: Some don’t feel anything for a while. But others get sudden swellings — especially around their joints or face — called Calabar swellings. They’re itchy, they move around, and they appear and disappear without warning. Then there’s the eye thing.

Sam: Which is the part I’m choosing to forget immediately.

Kate: So how do doctors even find it?

Heather: If they’re lucky — they see the worm in the eye and pull it out right then. But usually, they run a blood test during the day, between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m.

Sam: That’s oddly specific. Why?

Heather: Because Loa loa microfilariae — the baby worms — only circulate in the blood during daylight hours. They’re on a schedule.

Kate: Of course they are. They're punching a time clock.

Sam: So once they know it’s there, what do they do? Just… yank it?

Heather: If it’s in the eye? Yep. Local anesthetic, small incision, tweezers. But here’s the creepy part — sometimes the worm tries to retreat while they’re grabbing it.

Kate: Nope nope nope. That is not the surprise you want when doing your eyeliner.

Sam: I'm not getting close to my bathroom mirror again. Ever. What's going in my eyes is not my business. Do they get anesthesia for that? Do they get to be asleep?

Heather: They do, but you’re still awake. You can feel pressure. And you see it coming out.

Kate: I need to not know that.

Sam: That sounds like what I was told when I had my IUD put in and it was a lie. Is there medication?

Kate: You're gonna feel some pressure.

Heather: Yes — diethylcarbamazine, or DEC. It kills the adults and their offspring. But treatment needs to be done carefully. If someone has a heavy infection, killing off too many worms at once can cause a dangerous immune response — even neurological issues. So doctors might start with a gentler drug, like albendazole, to reduce the numbers first.

Kate: That's too many worms. Even the treatment sounds like a horror story.

Heather: The best option, of course, is prevention. In endemic areas, people wear long sleeves and pants, use insect repellents like DEET, and sometimes take weekly DEC under medical supervision to prevent new infections.

Sam: Umm that's horrific. DEET poisoning and exposure sounds like a way better alternative. So basically… don’t get bitten by deerflies?

Heather: Exactly. Avoid swampy, shaded areas during the day. Wear protective clothing. Treat your gear with permethrin.

Sam: Yeah I'll be taking a bath in it.

Heather: And if you’re traveling to an endemic area, ask your doctor about preventive medication.

Kate: Still thinking about a worm retreating across your eyeball.

Sam: Yeah, I’m never opening my eyes again. Like ever.

Heather: Well… maybe keep your eyes closed for the next one.

Heather: That was Loa loa—the one that wanders across your eye. But it pales next to the real dread of the next parasite.

Kate: Oh no. This is going to be worse, isn’t it?

Sam: What else could crawl in your eyes?

Heather: Meet Onchocerca volvulus—

Kate: That sounds dirty.

Sam: That sounds like an STD. Is that where this is going?

Kate: Not the volvolus!

Heather: I knew I wasn't going to be able to get through that one. OK, so let's just call that one the River Blindness parasite. This one doesn’t just visit your eye… it destroys it.

Heather: Imagine a small river village at dusk. Families gather after a long day. The air is thick, humid. Then come the blackflies—swarming in clouds, biting and feeding. Every bite could carry a larva of Onchocerca volvulus.

Kate: So these flies aren’t just biting for fun—they're delivering something sinister?

Heather: Exactly. These flies breed in fast-flowing rivers and infect people when they take a blood meal.

Sam: Wait. What? People are getting a blood meal? Right? No. People aren't doing the blood meal.

Heather: No. LOL Flies take the blood meal. People are just the unwilling buffet.

Kate: Oh good. I thought for a second we were switching into some strange Halloween vampire cult story.

Sam: (singing to Twilight song) Loa Loa.

Heather: Nope. Just your everyday river fly. But when it bites, it leaves behind larva that slip under your skin. Over months, they grow and mate under your skin, forming firm nodules—like little parasite bunkers. Inside those nodules, adult females can live up to 15 years and crank out microfilariae—tiny offspring that drift into your skin and eyes.

Sam: So they're literally breeding inside you?

Kate: I changed my mind. let's talk about vampires.

Heather: Yes—and it gets worse. These microfilariae spark a brutal immune response when they die. In the eye, that causes inflammation of the cornea. Over time, the scarring builds up. The surface clouds, vision dims, and eventually… blindness.

Kate: That’s horrifying. But is there something happening on the person's skin too?

Heather: Yes—and it's pretty dramatic. The skin often becomes discolored and leopard‑like—patchy depigmentation. In some, it thickens into “elephant skin,” or becomes rough like a reptile’s back—hence “lizard skin.” And the itching… it drives people to scratch until they bleed.

Sam: This is basically the slowest zombie infection ever.

Kate: Blindness or nonstop mortal-level itching… that’s a horror‑movie choice, right?

Heather: Honestly… which would you choose?

Sam: Uh. Death. Okay, but how bad is this—globally?

Heather: Onchocerciasis—or river blindness—is one of the leading causes of infectious blindness globally, Most of the 17–25 million infected people—mostly in sub-Saharan Africa near rivers—are at risk.

Kate: Have any communities turned this around?

Heather: Yes—through mass drug administration of ivermectin, donated by Merck. When taken once or twice yearly for 10–15 years, it dramatically reduces microfilariae and halts progression toward blindness. Some countries have even reached elimination.

Sam: Like. Wait. The ivermectin that people were like taking for COVID?

Heather: Same drug, totally different lane. Ivermectin is an antiparasitic—and this is one of the places it absolutely works, with decades of data and a global donation program behind it. But it doesn’t treat viruses, like for COVID it was a joke. But for river blindness, it’s a cornerstone of public health. When it works, we say so—and we use it.

Kate: So: parasites, yes. Viruses, no. Science hat back on.

Heather: Exactly. There's also a smart combo strategy. A course of doxycycline targets Wolbachia bacteria essential to the worm’s life cycle—essentially starving the adult. So this parasitic worm has some bacteria living in it that it needs to survive. And if you use an antibiotic to kill those bacteria you end up starving the adult worms so they stop reproducing and die off earlier. Programs use it in specific settings because it’s longer (about 4–6 weeks) and not for kids or pregnancy.

Sam: So the treatment is… a long haul?

Heather: Yes. Annual ivermectin for as long as the adult worms live—up to ~15 years—plus targeted doxycycline where appropriate. Stick with it, and communities can push to elimination. Some countries have even gotten to zero transmission.

Kate: Any gotchas?

Heather: One important safety note: in places where Loa loa is also common, people with very high Loa loa levels can have serious adverse events after ivermectin. Programs map and screen, and may use “test-and-not-treat” approaches so they can protect people and still fight river blindness

Sam: So the moral is: use the right drug for the right bug, the right way. Do the right thing. The targeted thing.

Heather: Exactly—and when we do, we save sight.

Kate: What about prevention before that?

Heather: Avoiding bites is key—wear repellent, long clothing, especially near rivers at dawn or dusk. On a larger scale, some control programs target blackfly populations through larvicide spraying.

Sam: So—just wearing long sleeves by the river could keep you from going blind.

Kate: I'm officially canceling the girls' trip to the river.

Heather: That sounds like a good idea.

Okay… deep breath, everyone. That was a lot of squirming and scratching for just the first two stories.

Kate: I’m not OK with this. I'm not over it. The part where you have to pin the worm down so it doesn’t escape the eye and then you see it leaving your eyeball? I am never blinking again.

Sam: I think my skin’s crawling, It's like when your kid's school has a lice outbreak and suddenly your head itches. It's like that but all over.

Heather: Well, good news — it’s snack break. And yes, it’s disturbingly on-theme. Kate, would you do the honors?

Kate: Don’t Blink S’mores and Deviled Eyes — because apparently, watching parasites crawl across eyeballs just isn’t enough unless you can eat something that looks like one.

Sam: I’m gonna need more Parasight Cider to cope with this.

Heather: Help yourself — just be careful when you drink it… the floating eyeballs have a way of locking eyes with you when you least expect it.

Kate: It’s always the staring.

Heather: Alright, everyone — snacks in hand, cider topped off, nerves barely intact…

Because the next story? This one doesn’t crawl… it dissolves.

Heather: River blindness devastates whole communities—and yet, what comes next doesn’t crawl... it dissolves.

Kate: I didn’t think losing your cornea could be more horrifying.

Sam: Wait… please don’t say it’s amoeba-related.

Heather: Oh, it gets worse. Meet Acanthamoeba keratitis—the eye‑eating amoeba.

Acanthamoeba Keratitis: The Eye‑Eating Amoeba

Heather: This one pops up in water—tap water, lakes, swimming pools… even tap-water-filled contact lens cases. It’s especially dangerous for anyone wearing contact lenses.

Kate: I did catch the pointed look in my direction. I am wearing contacts and I do occasionally have to rinse my little lens holder in tap water.

Heather: Oh my god. Don’t. Ever. Like seriously. Don't. The amoeba forms tough cysts and hides in tiny crevices, including your lens case.

Sam: I'm just not gonna put tap water near my face. I don't need to wash my face. Like ever. And nobody needs to shower. It's OK. Baths from the shoulders down. Forever,

Heather: That's a fantastic plan.

Sam: And oh god no hot tubs. can you imagine what comes out of your skin and put it in a tub full of people sluff?

Kate: Not people soup.

Heather: People soup!

Sam: I said people sluff! Not soup. To be clear.

Heather: She said soup!

Sam: Oh, well, yeah, it's like a really delicate broth. Cause it's just like skin sluff.

Kate: Just a slow marinade.

Heather: A delicate broth!

Sam: For like sipping on when you're sick. It's getting to be that time when we get sick so you can have some people soup.

Heather: Oh my god. OK. So what are the early signs if you get this? Think redness, pain, a gritty feeling—as if your eye’s hosting its own sandstorm.

Sam: Cue Dune music.

Kate: I'm itchy. My eyes are itchy. That already sounds brutal.

Heather: It sounds like somebody washed their lens case in tap water. Well you're in luck cuz it gets worse. The amoeba burrows deeper into the cornea, creating ulcers—and in advanced cases, it can destroy the cornea entirely. You may lose vision, or even require surgical removal.

Kate: Why do you hate me? Wait. How common is this?

Sam: Surgical removal? Surgical removal of your eye or surgical removal of the amoeba guy? Or both, I guess?

Kate: The cornea, right?

Heather: Yeah, surgical removal of the cornea.

Kate: Cool.

Sam: Horrific. I choose death.

Kate: I was thinking about Lasik, but no.

Heather: Could you imagine if you're doing Lasik and someone had a worm in their eye?

Kate: How common is this?

Heather: It’s rare—about 1 to 2 cases per million contact‑lens wearers each year in the U.S. But among those infected, nearly 90% wear contacts. And exposure to water while wearing them is the biggest red flag.

Sam: Well, I already feel like I'm winning cuz I don't wear contacts cuz I can't touch my eyeballs. So… hygiene lapses and water contact—what’s the actual survival rate?

Heather: Treatment can be brutal. You need powerful eye drops—biguanides like PHMB or chlorhexidine—targeting the active amoeba, but cysts are incredibly resistant.

And if it progresses, you may need to debride (that’s surgically scrape) the cornea or, in severe cases, get a corneal transplant. But even then, graft survival is poor—much worse with this than with bacterial or viral infections.

Kate: As a contact wearer I am feeling very personally attacked.

Sam: I'm just becoming more traumatized. I really like my eyes.

Heather: I cannot in good conscience not pause here and give a warning: Never rinse or store your lenses in tap water. Use only sterile solutions and follow hygiene to the letter. OK? Anybody out there with lenses...do better than Kate.

Sam: Uh can I ask a question?

Heather: Sure:

Sam: I'm thinking High school science lab and presumable every other lab in the entire world you've got like the emergency eye rinse station? That is tap water and it is like force-drilled into your eye holes. Should I just choose the chemicals?

Heather: No, um, go ahead and use that but don't do it while you have contacts in. Take your contacts out and then rinse your eyes.

Sam: Fair enough. I'm sure that's like step one in the infographic anyways.

Heather: Great question, though.

Kate: I'm gonna have to start being better about all of the things that I do with my contact lenses. I could never survive with permanent vision damage. I have to be able to read.

Heather: That’s the thing—if detected early, before deep ulceration, medical treatment can clear it. But delays are common because symptoms mimic viral or bacterial keratitis—and misdiagnosis can make it worse, especially if steroids are prescribed.

Sam: So how long is treatment, or recovery?

Heather: Often weeks to months of intensive therapy—drops, regular check‑ups. If a graft is needed, recovery is lengthy and not guaranteed.

Kate: Basically: treat fast or lose your eye.

Heather: Basically. So get your water habits clean. Sterile. Simple.

Because the real horror here… is what can hide in plain tap water.

Heather: Just when you thought eye parasites had reached maximum creep…

Kate: Yeah... what’s next? Fistful of fish worms for my face?

Samantha: I'm sorry what the fuck is a goat yoga?

Heather: That's our next topic!

Sam: No that's not a real thing!

Heather: Yes it is!

Sam: Excuse me?

Heather: Yes!

Sam: Goat yoga worms dangling in my eye.

Heather: Exactly

Kate: Who thought it's a good idea to have a goat put its butt in your face anyway?

Heather: Excellent question, Kate.

Sam: I'm just thinking like picturing goats doing the acrobatic yoga with the curtain things.

Heather: Have you seen people do yoga with goats?

Sam: No. That seems stupid.

Heather: It's a thing!

Kate: It's a thing!

Heather: They like get on the ground and the goat stands on their back and walks around and licks their face.

Kate: and it's like and Instagram thing.

Sam: Only people who live in the city and have never actually like met a goat would do that. That's the stupidist thing I've ever heard. I have to google this.

Heather: I can't believe you haven't heard of this.

Kate: Goat yoga. Yeah. Sometimes the goats have pajamas on just for you know... cuteness.

Heather: Meet Thelazia gulosa—the goat yoga eyeworm.

Thelazia gulosa: The Goat Yoga Eyeworm

Heather : OK so this happened in 2016, in Oregon. A woman—years later, identified as Abby—started to feel something odd in her eye: like an eyelash she couldn’t reach. So she pinched her eyelid... and pulled out a tiny translucent worm.

Then… 13 more over the next few weeks. Fourteen in all.

Kate: No. We're officially canceling goat yoga. It's done it's canceled.

Samantha: I bet the goats were like, “Naaamaaaste,” like Jesus Christ. I can't believe that this is real.

Heather: Yep, so, the worm—Thelazia gulosa—normally infects cattle and sometimes horses. These worms hang out in the tear ducts or under the eyelids of animals.

Sam: So there's a joke to be made here but I'm dying... how did it jump from cows to a human? Are we just snuggling?

Heather: Here’s the science: face flies—those flies that hang around cattle and horses—feed on tear secretions. When a fly visits an infected cow, it picks up worm larvae. A few weeks later, when it lands again… bingo. The larvae are deposited onto the eye of another animal—or, in rare cases, a human.

Kate: So the goat yoga thing was just… poetic misfortune? She's trying to be healthy and instead. Goat. Worm. Eyeball situation.

Heather: Exactly. A stray face fly that was flying around the goat, right? That's why it was there. And her eye looks tasty! That’s how we got the first-ever recorded U.S. human infection with Thelazia gulosa.

Samantha: Fourteen worms… did she go blind? That's a lot of worms.

Heather: That is a terrifying amount of worms. But no she didn't go blind. They removed each one, and she recovered fully. So I guess she didn't pull them all out then. They removed them. But if these worms hang around, they can cause inflammation, corneal scarring, and even vision loss.

Kate: Goes to goat yoga... comes home with goat eyeworms.

Samantha: “Eyeworm” sounds like a bad metal band name. I don't like it.

Kate: Different kind of music. So, is this going to be a regular thing for humans now?

Heather: Experts say no — this is likely a fluke event. The worm hasn’t evolved to infect humans regularly. But it reminds us how close—and how weird—the wildlife-human interface really is. And yes, parasitologists — I hear the pun. But technically this wasn’t a fluke… it was a nematode.

Samantha: So what am I supposed to do if I feel something in my eye on a Tuesday other than like get a fork and scoop it out cuz this is now going to ruin...every time I get like cuz I do get eyelashes in my eyes and it's terrible but now it's a worm. Immediately we have jumped from oh I have an eyelash to oh I have a rare eye worm. So like what am I supposed to do now?

Heather: Get to an ophthalmologist immediately. So most of these worms stay on the eye surface, so removal is usually effective. Quick action can spare your vision.

Kate: Thank goodness it can be fixed. However I am changing my future plans about having goats.

Heather: Yeah. That sucks, I like goats.

Samantha: I'm out—I’ll stick to regular yoga. And the goats can stay outside.

Heather: Wise choice.

Heather: Well, friends… that brings us to the end of tonight’s Outbreak After Dark. We’ve seen worms that wander across your eyes, parasites that scar them blind, amoebas that dissolve them, and even an eyeworm hitching a ride at goat yoga.

Kate: I, for one, will be wearing safety goggles in the shower from now on. And I will never us tap water near my contacts.

Heather: Excellent

Sam: I’m I'm wearing safety goggles all the time not just the shower and i will be sleeping with my eyes duct-taped shut and goggles over them.

Heather: Before we go, it’s time for the first-ever “Nope Trophy.” Which of tonight’s four horrors wins the biggest Nope for you?

Sam: It's got to be the amoeba for me. Amoebas in general just freak me out immediately like you say amoeba and I go...huh so I think it's just gotta be amoeba. Yeah no.

Kate: I think for me it's gonna have to be river blindness just the fact that the worms live for 15 years. I mean even having a relationship that long...so having one with a worm...no.

That's common law marriage. like Damn...make sure to get those tax benefits.

Heather: Yeah river blindness just the fact that it ends in blindness so often like that terrifies me.

Heather: And since this is our Halloween debut, here’s your party reminder: if you’re dressing up as a zombie, vampire, or witch this week… remember, the real monsters don’t wear costumes. They’re small enough to fit in your tear ducts.

Kate: Thank you for that. That is just what I wanted to picture at a Halloween party.

Samantha: Nothing says “festive” like amoeba eye-melt.

Kate: Ooh that should've been one of our snacks!

Heather: Ahh! Dang it.

Kate: Oh for sure.

Sam: It sounds like a sandwich. I'm gonna be honest with you like that sounds like a grilled cheese and tomato soup.

Heather: That's a great Halloween sandwich! Or it would've been good for our s'mores amoeba eye melt.

Sam: Next time. So little time so many snacks.

Heather: So raise your glass — cider, cocoa, or whatever keeps you warm — to the creepiest windows to the soul we’ve ever peered through. Here’s to seeing another sunrise… with both eyes still our own.

By the fire we meet…

With food, drink, and infectious creep…

This is Outbreak After Dark.

Happy Halloween, everyone. And remember — Outbreak After Dark will be back once a month, with new stories waiting in the shadows. Until then… sleep tight. And don’t let the worms bite.

.

.png)

Comments