RSV: Symptoms, Spread, and Prevention

- Heather McSharry, PhD

- 12 hours ago

- 14 min read

Summary

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is one of the most common respiratory viruses in the world — and one of the least well understood outside pediatric and infectious disease circles. Nearly every child is infected by age two, and RSV continues to circulate throughout adulthood, sometimes causing serious illness in infants, older adults, and people with underlying health conditions.

In this episode of Infectious Dose, I break down what RSV actually is, how it spreads, how long it incubates, and what illness typically looks like — from mild cold-like symptoms to signs that require urgent medical care. We walk through what parents and caregivers can safely manage at home, how to recognize red flags related to breathing and hydration, and when to seek emergency care.

The episode also covers what’s changed recently: rising RSV activity in parts of the U.S., alongside strong real-world evidence that newer prevention tools — including maternal vaccination and long-acting monoclonal antibodies — are significantly reducing RSV hospitalizations in infants where they’re used. This is a practical, evidence-based guide to RSV, designed to inform without alarming and to help families feel prepared rather than panicked.

Listen here or scroll down to read full episode.

Full Episode

Before we get into today’s episode on RSV, you might hear in my voice that I’m under the weather — yes, I have the flu.

And how did I get the flu, despite getting my flu shot? Well, my son and I both got infected after spending time with someone who didn’t get vaccinated — someone who also got very sick.

My ex-husband — who says he never gets sick and doesn’t need vaccines — wound up testing positive for influenza, went to urgent care, needed Tamiflu, and was hospitalized with dehydration and high fever.

Then our son got sick. Then I got sick.

So even though I’m vaccinated and my case is relatively mild, I’m recording today with a flu voice — all because one person chose not to get vaccinated.

It’s a real-world example of how individual choices ripple outward.

So, with this flu-raspy voice in tow, let’s talk about another virus that hits hard: RSV.

It's a virus every parent and caregiver should understand — a respiratory virus that’s actually one of the most common causes of severe illness in babies and an important seasonal pathogen for older adults and others at risk: Respiratory Syncytial Virus, or RSV.

WHAT’S GOING ON RIGHT NOW

Currently, health authorities in Pennsylvania are reporting a rapid increase in lab-confirmed RSV cases this respiratory virus season. According to recent news reports, more than 10,000 RSV cases have been recorded in that state since the season began last fall — and that increase has state officials watching closely.

And this fits into a broader picture: RSV season typically runs in the fall and winter in the Northern Hemisphere, and recent surveillance suggests ongoing circulation alongside flu and other respiratory viruses. Activity in some regions remains elevated compared with recent years.

At the same time, in places where preventive measures like vaccines and monoclonal antibody products have been taken up, early data show dramatic reductions in hospitalizations among infants. Analyses presented last week indicate that a long-acting monoclonal antibody called nirsevimab has cut infant RSV hospitalizations by roughly 83% in some settings.

We’ll unpack what all that means in a moment, but first — what is RSV?

RESPIRATORY SYNCYTIAL VIRUS — THE BASICS

RSV is a respiratory virus — specifically, a single-stranded RNA virus in the Pneumoviridae family. That puts it in the same broad neighborhood as a few other respiratory viruses you may have heard of, like human metapneumovirus, which also causes cold- and flu-like illness and can be dangerous for infants and older adults.

At a structural level, RSV is what we call an enveloped virus. That means its genetic material is wrapped in a fatty outer membrane stolen from the last cell it infected. Embedded in that membrane are viral proteins that act like grappling hooks — helping the virus attach to, enter, and fuse with our respiratory cells.

What’s inside the virus

Inside that envelope is RSV’s genome, which is made of negative-sense RNA.

That phrase sounds technical, but here’s what it means in plain language:

Our cells read genetic instructions like a recipe written in English.

RSV’s RNA is written backwards.

Before a cell can make anything from it, the virus has to bring its own molecular “translator.”

So RSV doesn’t just deliver its RNA and walk away — it carries its own RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, an enzyme that converts that backward RNA into a readable form. In fact, all negative-sense RNA viruses carry their own RNA polymerase

How RSV replicates

Once RSV gets inside a cell lining your nose, throat, or lungs, the process looks roughly like this:

Attachment – RSV binds to the surface of a respiratory cell using its surface proteins, especially the F protein, short for “fusion protein.”

Fusion and entry – The virus fuses its envelope with the cell membrane and releases its RNA into the cell.

Replication – Using its own polymerase, RSV makes copies of its genome and produces viral proteins.

Assembly – New virus particles are assembled inside the cell.

Release – Fresh RSV particles bud out, ready to infect neighboring cells.

That fusion protein is especially important — it’s not just how RSV gets into cells, it’s also how infected cells can fuse together into large clumps called syncytia. That’s actually where the virus gets its name: respiratory syncytial virus.

Those fused cells interfere with normal airflow in small airways, which helps explain why RSV can be so dangerous in tiny lungs.

Why reinfections happen

RSV does not produce long-lasting immunity. Even after infection, RSV induces only partial and short-lived immunity, which means reinfection is common — though subsequent cases are often less severe.

That’s why:

Nearly every child has been infected by age two

Most people are infected again and again throughout life

RSV can still cause severe disease in older adults and immunocompromised people

The virus evolves slowly, but it doesn’t need to evolve rapidly like flu or COVID to keep spreading — it relies on imperfect immune memory and constant exposure.

RSV’s viral relatives

RSV is part of a family of viruses that specialize in the respiratory tract. Some relatives you might recognize or have heard mentioned by doctors include:

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) – very similar seasonality and symptoms

Parainfluenza viruses – common causes of croup in young children

These viruses tend to circulate in the same seasons and hit similar vulnerable populations, which is why pediatric hospitals often see waves of multiple respiratory viruses at once.

“So RSV isn’t exotic or rare — it’s structurally simple, brutally efficient, and perfectly adapted to spreading through small airways in the people who can least afford it.”

HOW RSV SPREADS — WHY IT’S SO HARD TO AVOID

RSV spreads the way most respiratory viruses do — but it’s especially good at it.

When someone with RSV coughs, sneezes, talks, laughs, or even breathes, they release virus-containing droplets into the air. Some of those droplets are larger and fall quickly onto nearby surfaces. Others are smaller aerosols that can linger briefly in the air, especially indoors with poor ventilation.

If you’re close by — holding a baby, sitting next to someone on the couch, leaning in during a conversation — those droplets can land directly on your nose, mouth, or eyes, which are essentially open doors into the respiratory tract.

But RSV doesn’t stop there.

RSV on surfaces

RSV can also spread through contact with contaminated surfaces, and this is especially important with infants and young children.

The virus can survive:

Up to 6 hours on hard surfaces like tables, crib rails, toys, and doorknobs, and

30–60 minutes on hands or soft surfaces like clothing, tissues, and bedding, depending on humidity and temperature.

So if someone with RSV wipes their nose, coughs into their hand, or sneezes nearby — and then touches a toy, a bottle, or a countertop — the virus can be left behind.

When another person touches that surface and then touches their eyes, nose, or mouth, infection can occur.

This is why RSV spreads so efficiently in:

Daycares and schools

Pediatric wards and NICUs

Households with young children

Anywhere people are in close contact for long periods of time

And it’s why hand-to-face contact matters so much — especially for babies, who are constantly putting their hands and objects into their mouths.

Why babies are particularly exposed

Infants are often infected not because they are going places — but because RSV is brought to them.

Older siblings, parents, caregivers, and visitors can carry RSV with mild cold-like symptoms and unknowingly pass it along through close contact, kisses, shared spaces, and shared objects.

TIMING AND INCUBATION — WHEN SYMPTOMS SHOW UP

After someone is exposed to RSV, there’s an incubation period — the time between infection and the start of symptoms.

For RSV, that window is typically 2 to 8 days, with most people developing symptoms around 4 to 6 days after exposure.

During this time, the virus is quietly replicating in the cells lining the respiratory tract — building up numbers before symptoms become noticeable.

When people are contagious

People with RSV are usually contagious for about 3 to 8 days after symptoms begin.

But — and this is important — infants and people with weakened immune systems can shed virus for much longer, sometimes for several weeks. That means they can continue spreading RSV even after symptoms seem to be improving.

This extended shedding is one reason RSV is so difficult to control in neonatal units and pediatric settings.

Mild symptoms don’t mean low risk

One of the trickiest things about RSV is that people are often contagious when their symptoms are mild — or before they realize they’re sick at all.

An adult with what feels like a runny nose or mild cough can easily transmit RSV to an infant, where the same virus can cause serious lower-lung disease.

That mismatch — mild illness in one person, severe illness in another — is a big part of what makes RSV dangerous at a population level.

So RSV doesn’t need dramatic symptoms or exotic transmission routes — it spreads through everyday closeness, shared air, shared hands, and shared spaces.

SYMPTOMS — WHAT’S NORMAL, WHAT’S NOT, AND WHEN TO ACT

For most people, RSV looks a lot like a common cold.

In older children and adults — and even in many babies — symptoms often include:

Runny or stuffy nose

Sneezing

Cough

Mild fever

Sore throat

Decreased appetite

General fussiness or fatigue

In these cases, RSV usually runs its course over about a week, and people recover at home with rest, fluids, and comfort care.

And that’s important to say out loud:👉 Most RSV infections are mild.

Why RSV is different in babies

Where RSV becomes concerning is when it moves from the upper airway — the nose and throat — down into the small airways of the lungs.

Infants, especially those under 6 months, have:

Very small airways

Immature immune systems

Limited ability to compensate when breathing becomes harder

That’s why the same virus that causes a mild cold in an adult can cause significant breathing trouble in a baby.

WATCH, CALL, OR GO NOW

🟢 You can usually watch and manage at home if:

Breathing looks comfortable

Your child is feeding reasonably well

Wet diapers are normal

Skin color looks normal

Fever is mild and responding to medication

A congested baby who’s cranky but breathing comfortably and still eating is usually okay — but if you have any concerns at all CALL YOUR DOCTOR. Better safe than sorry. And yes, I may have been on a first-name basis with every nurse in our pediatric clinic. Maybe.

🟡 Now if you see these symptoms then Call your pediatrician or doctor right away. They can triage over the phone and tell you to come in or not:

Breathing seems faster than usual

Worsening cough

Trouble feeding because of congestion or fatigue

Fewer wet diapers than normal

Fever that’s persistent or rising

You just feel something isn’t right

Trust that instinct. Pediatricians would much rather talk you through a mild case than see a baby too late.

🔴 Go to urgent care or the ER immediately if you see:

Labored breathing — chest pulling in under the ribs or at the neck

Nostrils flaring with each breath

Grunting or wheezing

Blue or gray color around lips, mouth, or fingernails

Extreme lethargy — hard to wake or not responding normally

Refusing to eat or drink

Very few wet diapers — a sign of dehydration

These are signs that RSV may be affecting the lower lungs and oxygen levels — and that medical support may be needed.

WHEN TO DRIVE — AND WHEN TO CALL AN AMBULANCE -

This was something I worried over when my son was a baby. And a toddler. And a child. And a teen. And an adult. Not gonna lie it never ends.

So if you’re seeing signs that RSV is affecting breathing, it’s absolutely appropriate to seek emergency care. The next question is how to get there.

🚗 It’s usually okay to drive to the ER if:

Your child is breathing fast or working harder than normal but is awake and responsive

Skin color is normal

They’re crying, interacting, or reacting to you

You can safely secure them in a car seat

You live reasonably close to emergency care

If you can get to the ER quickly and safely, driving is often the fastest option.

🚑 Call an ambulance immediately if:

Skin, lips, or fingernails look blue or gray

Breathing is severely labored, irregular, or slowing

Your child is very hard to wake, limp, or unresponsive

There is grunting with every breath or long pauses between breaths

A baby appears to stop breathing, even briefly

You feel unable to transport safely

An ambulance isn’t just transportation — it brings oxygen, monitoring, and trained medical care that can start the moment they arrive.

❤️ Trust your judgment

If you’re unsure — or if your instinct says something is seriously wrong — calling 911 is always the right call.

No emergency responder will ever fault you for calling when a child is struggling to breathe.

Breathing emergencies aren’t the time to debate whether something is ‘bad enough.’ If you’re worried you can’t get there safely, call for help.

Please understand that I am not giving medical advice here...but the American Academy of Pediatrics has excellent guidance on RSV for parents. I’ve linked to their page ‘RSV: When It’s More Than Just a Cold’ in the show notes and blog post at infectioussode.com, it walks through common symptoms, when to call your pediatrician, and when to seek urgent care or emergency help. It also outlines basic supportive care — saline nasal drops, cool-mist humidifier, fluids, temperature management with acetaminophen or ibuprofen (with age-specific notes), and what not to do (e.g., avoid aspirin or cough/cold medicines in young children). These are general guidelines but please always check with your pediatrician as they know the medical history of your child and family that are critical for addressing appropriate individual medical needs. Here is a video from them as well.

SO WHY DO DOCTORS TAKE RSV SERIOUSLY?

In some cases, RSV can lead to more serious complications, particularly in infants, older adults, and people with underlying health conditions.

The most common include:

Bronchiolitis — inflammation and blockage of the smallest airways in the lungs

Pneumonia — infection deeper in the lung tissue

Low oxygen levels, requiring supplemental oxygen

Respiratory failure, sometimes requiring intensive care

Worsening of chronic lung or heart disease

Globally, RSV is one of the leading causes of hospitalization in young children. Each year, an estimated 3.6 million children under five are hospitalized with RSV, and close to 100,000 deaths are attributed to RSV worldwide — most in low- and middle-income countries where access to supportive care is limited.

That global burden is one reason RSV prevention has become such a major public-health priority.

Most RSV infections are uncomfortable — not dangerous. The key is knowing when breathing becomes the problem, not the congestion or the cough.

TREATMENT — WHAT WE CAN DO

There’s no specific antiviral that cures RSV once you’re infected — treatment is mainly supportive:

Rest and hydration

Fever reducers like acetaminophen

Oxygen support in hospital for severe cases

In high-risk infants, older monoclonal antibodies like palivizumab have been used for years to prevent severe disease. But, Palivizumab was limited to very high-risk infants and required monthly injections — a barrier that nirsevimab and clesrovimab are helping overcome. And there's more good news!

PREVENTION — NOW WITH REAL OPTIONS

For decades, we had no licensed vaccine for RSV. In the last few years, that has started to change.

👶 For babies — passive protection

Infants can now be protected before or shortly after birth using:

nirsevimab (Beyfortus) – a long-acting monoclonal antibody given as a single shot that provides passive protection through the RSV season. It doesn’t work by activating the infant’s immune system like a vaccine does — instead it directly supplies antibodies that neutralize the virus.

Real-world data show that nirsevimab reduces RSV hospitalizations by roughly 80-90% in settings where it’s used and cuts ICU admissions and severe disease significantly.

In fact, early rollout of nirsevimab was so successful that some areas experienced supply constraints, highlighting both its value and the need for widespread access.

There’s also clesrovimab (Enflonsia), another long-acting monoclonal antibody approved in the U.S. to prevent severe RSV disease in infants.

👵 For older adults

There are also active RSV vaccines licensed for older adults (like Arexvy, Abrysvo, and others), which stimulate the immune system to protect against severe RSV disease later in life. These vaccines are now recommended for adults 60+ based on shared clinical decision-making with a provider, per CDC guidelines.

And for pregnant people we have:

Maternal RSV vaccines like Abrysvo — Pfizer’s RSVpreF vaccine — are given in late pregnancy to generate antibodies that transfer across the placenta and help protect the newborn during their first months of life. Abrysvo™ was approved for use during pregnancy in the United States in 2023, and it has since been authorized in multiple other countries, including Canada, the UK, the EU, Japan, Australia, and several European Economic Area countries. Exact timing recommendations can vary by country based on local regulatory and immunization guidance.

In the United States, Abrysvo is the only RSV vaccine approved for use during pregnancy. It is given as a single dose at 32 through 36 weeks of gestation to help protect infants from birth through 6 months of age. In some other countries, vaccination may be offered earlier in pregnancy — often beginning around 28 weeks — depending on national guidelines.

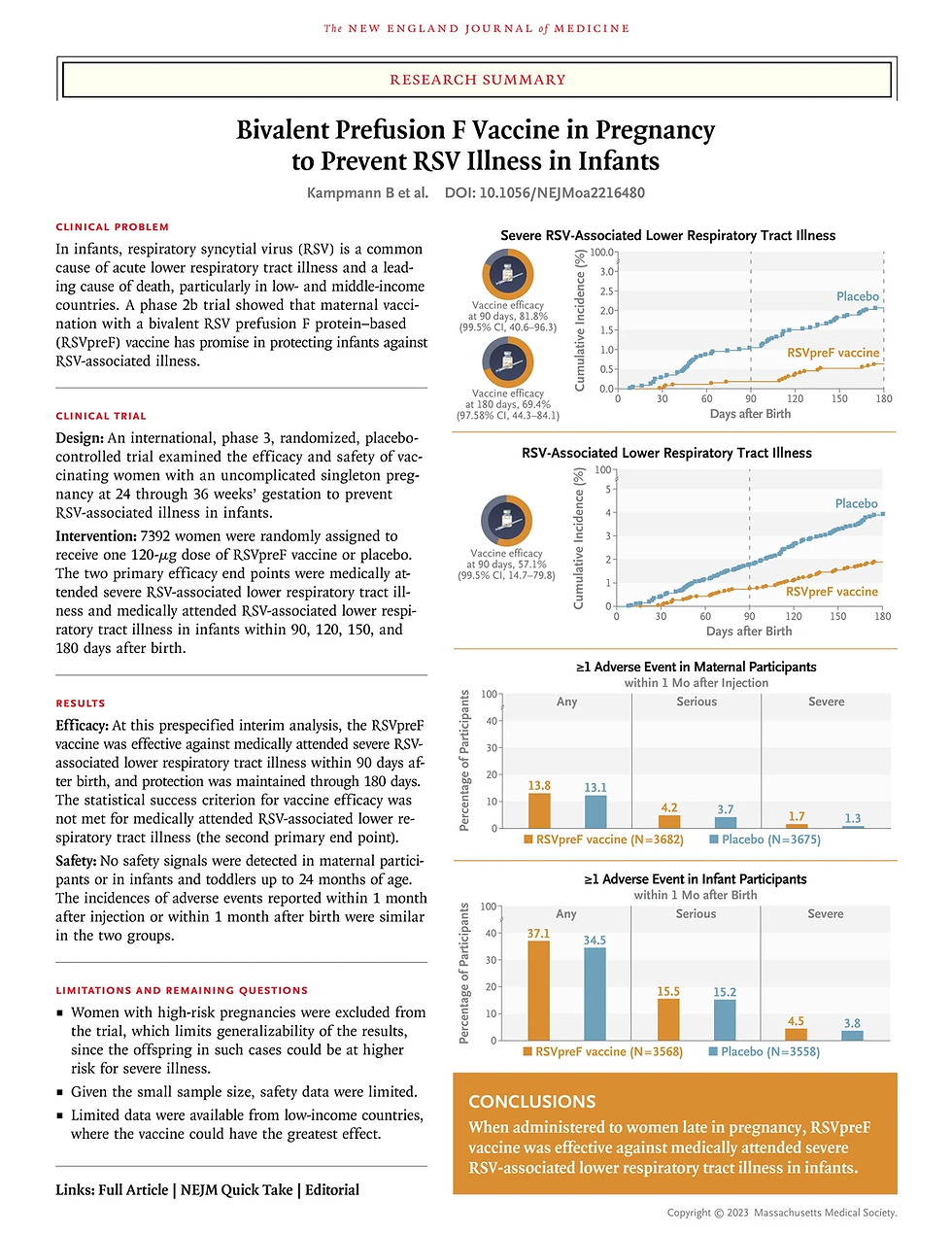

Clinical trials show that when Abrysvo is given during pregnancy, it significantly reduces the risk of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract illness in infants during their first six months of life. In fact, to the right is a summary of the clinical trial data linked above.

So what's in this vaccine?

ABRYSVO (Pfizer) is a sterile solution for intramuscular injection. Here’s what’s in it, according to the package insert:

Antigen:

RSV stabilized prefusion F proteins: preF A and preF B

These are proteins found on the surface of the virus it uses to enter cells. Targeting this prefusion form is key to generating protective antibodies.

Stabilizers:

Tromethamine (Tris) – helps maintain the pH of the vaccine formulation

Tromethamine hydrochloride (Tris HCl) – also helps maintain pH

Sucrose – helps protect the vaccine during freezing or temperature fluctuations

Mannitol – provides structural stability and helps prevent protein aggregation during manufacturing and storage

Polysorbate 80 (Tween 80) – a surfactant that prevents protein aggregation and helps keep the vaccine evenly mixed

Sodium chloride – adjusts tonicity so the vaccine’s osmolarity is similar to that of human cells, minimizing irritation and supporting safe delivery

Preservatives:

Abrysvo contains no preservatives.

Residuals: During manufacturing, trace amounts of host cell proteins (≤0.1% by weight) and residual DNA (<0.4 nanograms per milligram of total protein) may remain.

These residuals are present at extremely low levels, are tightly regulated, and do not pose a health risk.

NOTE: Because of the changes RFKjr made to vaccine recommendations, ACOG released updated guidance on maternal immunization for COVID-19, Influenza, and RSV on 8/22/2025. The updated recommendations in support of vaccination are consistent with ACOG’s previous recommendations and also reflect a large and growing body of research and data regarding the safety and benefits of maternal immunization.

Vaccination and antibody therapy have been linked to lower infant hospitalization rates, and early data from national immunization surveys show coverage climbing where programs are in place. This is fantastic news for our babies.

WHAT IT ALL MEANS IN PRACTICAL TERMS

RSV is common, and most cases are mild. But for the youngest babies and the oldest adults, or anyone with a fragile immune system, it can be serious.

The good news is that we finally have tools — maternal vaccination and long-acting antibodies — that are dramatically reducing severe disease in infants where they’re being used. But uptake varies, and public awareness isn’t where it needs to be.

And right now, even as vaccines help protect some infants, we’re seeing increases in RSV circulation in parts of the U.S. this winter, reminding us that RSV, like flu, is still a seasonal threat we need to take seriously.

That’s it for today’s episode on RSV. If you have questions you want tackled in future shows send them my way.

Thanks for listening. Don't miss your next dose of infectious disease science right here. Until then, stay healthy, stay informed and spread knowledge not diseases.

REFERENCES

.png)

Comments